Opsin evolution: ancestral introns: Difference between revisions

Tomemerald (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Tomemerald (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Introns within coding regions of opsin genes can potentially provide an independent (or supplemental) means of organizing known opsins and and classifying new ones. This becomes especially important as the universe of opsins has expanded to include rhabdomeric opsins within deuterostomes, ciliary opsins within protostomes, and novel opsins from cnidarians which might be otherwise difficult to separate from rhodopsin-superfamily non-opsins and generic GPCR. | Introns within coding regions of opsin genes can potentially provide an independent (or supplemental) means of organizing known opsins and and classifying new ones. This becomes especially important as the universe of opsins has expanded to include rhabdomeric opsins within deuterostomes, ciliary opsins within protostomes, and novel opsins from cnidarians which might be otherwise difficult to separate from rhodopsin-superfamily non-opsins and generic GPCR. | ||

Changes in intron pattern consititue a category of rare genetic event (RGE). Other RGEs relevent to opsins include coding indels (insertion or deletion of amino acies) and gene order rearrangements along a chromosome. RGEs are characters that can be used in gene tree analyses and reconstruction of ancestral states. Each type of RGE has its own intrinsic time scale that makes it useful on aspects of opsin evolution over comparable time frames. Intron patterns are extremely conserved, making them useless (stay the same) over mammalian, even vertebrate, time scales but appropriate to Eumetazoan. Indels are quite conserved but informative within opsins over shorter periods. Gene order is only moderately conserved, | Changes in intron pattern consititue a category of rare genetic event (RGE). Other RGEs relevent to opsins include coding indels (insertion or deletion of amino acies) and gene order rearrangements along a chromosome. RGEs are characters that can be used in gene tree analyses and reconstruction of ancestral states. Each type of RGE has its own intrinsic time scale that makes it useful on aspects of opsin evolution over comparable time frames. Intron patterns are extremely conserved, making them useless (stay the same) over mammalian, even vertebrate, time scales but appropriate to Eumetazoan. Indels are quite conserved but informative within opsins over shorter periods. Gene order is only moderately conserved within Bilatera, more commonly it is completely washed out. All RGEs are subject to some degree of homoplasy (multiple independent origins). | ||

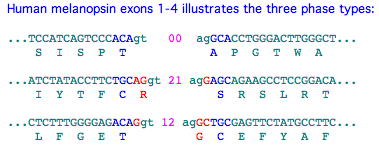

The intron pattern consists of two parameters, location and phase (codon splitting across two exons): | The intron pattern consists of two parameters, location and phase (codon splitting across two exons): | ||

Revision as of 10:59, 18 December 2007

Introns within coding regions of opsin genes can potentially provide an independent (or supplemental) means of organizing known opsins and and classifying new ones. This becomes especially important as the universe of opsins has expanded to include rhabdomeric opsins within deuterostomes, ciliary opsins within protostomes, and novel opsins from cnidarians which might be otherwise difficult to separate from rhodopsin-superfamily non-opsins and generic GPCR.

Changes in intron pattern consititue a category of rare genetic event (RGE). Other RGEs relevent to opsins include coding indels (insertion or deletion of amino acies) and gene order rearrangements along a chromosome. RGEs are characters that can be used in gene tree analyses and reconstruction of ancestral states. Each type of RGE has its own intrinsic time scale that makes it useful on aspects of opsin evolution over comparable time frames. Intron patterns are extremely conserved, making them useless (stay the same) over mammalian, even vertebrate, time scales but appropriate to Eumetazoan. Indels are quite conserved but informative within opsins over shorter periods. Gene order is only moderately conserved within Bilatera, more commonly it is completely washed out. All RGEs are subject to some degree of homoplasy (multiple independent origins).

The intron pattern consists of two parameters, location and phase (codon splitting across two exons):

Location is easy to specify homologically because opsins contain numerous invariant or near-invariant residues sprinkled along their length that unambiguously anchor alignments. The main potential difficulty occurs near an indel (insertion or deletion). However indels are very rarely fixed in the core region of opsins because the transmembrane helices (3.4 residues per turn) do not tolerate that disruption of their bundle associations or retinal tuning or membrane spanning lengths and because the cytoplasmic and extracellular loop regions are generally too short or otherwise significantly engaged in conserved interactions with other signaling molecules. Indels in the amino and carboxy termini, which in some opsin classes are extended and poorly conserved, are exceptions to this.

It's quite possible for more or less the same intron location to arise repeatedly (convergent evolution), especially when 'same' is slightly muddled by indel ambiguity. However phase determination can often disambiguate this issue. Here we must briefly review MolBio 101 because many opsin papers exhibit total unawareness of the phase concept:

Three possibilities exist for intron phase: In phase 00, the splice donor (GT in all known opsins) follows immediately after last triplet codon of an exon and the splice acceptor (AG in all known opsins) can immediately precede the first codon of the next exon. In phase 12, an extra basepair follows the last complete triplet codon and precede the start of the splice donor; two extra base pairs (which fill out the split codon and preserve reading frame) follow the splice acceptor but precede the next complete codon. In phase 21 introns, the overhang is 2 bp at the donor complemented by 1 bp overhang at the acceptor, together a new 3 bp triplet codon.

>MEL1_homSap Homo sapiens (human) Gq 483 NM_033282 melanopsin OPN4 0 MNPPSGPRVPPSPTQEPSCMATPAPPSWWDSSQSSISSLGRLPSISPT 0 0 APGTWAAAWVPLPTVDVPDHAHYTLGTVILLVGLTGMLGNLTVIYTFCR 2 1 SRSLRTPANMFIINLAVSDFLMSFTQAPVFFTSSLYKQWLFGET 1 ...

It's useful to indicate phase information within the fasta representation of a sequence. That's done here by line breaks between exons with associated phase overhangs shown by numbers. These numbers are ignored by the vast majority of web software tools so the extra characters do not to be purged before say a blast query. By convention, the initial methionine is preceded by a 0 even though it is almost always part of a larger 5' UTR. Similarily the stop codon asterisk is followed by a 0 even though it is almost always part of a longer 3' UTR. One last convention: the 'extra' amino acid formed by 12 or 21 introns is assigned to the 2 side of the exon break. It's often given incorrectly in Blast output because that tool is not aware of exon breaks and often extends alignments past them into a translated intron.

Normally, phase is determined by aligning by blastn of a transcript (processed already by the cell to remove introns) against genomic. If genomic is not available, the transcript can by intronated be comparison to a phylogenetically close orthologous gene.

For example, full length transcripts were sequenced for various opsins from the amphioxus Branchiostoma belcheri. However the genome project is not there but over in Branchiostoma floridae. So the B. belcheri proteins need to be placed within the B. floridae, which is most conveniently done using Blat on the UCSC genome browser. Exon boundaries are then read off from the alignment details page using 3-frame translation in a second web browser tab at Expasy to ensure smooth reading frame joins and uBlastx against the opsin collection in a third to monitor alignment. That process accurately intronates the presumptive ortholog in B. floridae. Finally B. belcheri is back-intronated by alignment. That amounts to a testable prediction of intron pattern in that species.

This won't be accurate if B. belcheri has gained or lost introns since the two species diverged. However, outside of certain rogue species, introns typically have a "half-life" of perhaps 5 billion years of branch length, many multiples of the divergence time here. (They're much more conserved than amino acid sequence.) Consequently the inferred gene model will be correct 99% of the time. However every sequence in the Opsin Classifier that originated in a genome project was independently intronated within that project, never by homology. And some species without genome projects (like Platynereis) have the occasional large contig containing an opsin.

In practise, it is easy to make small mistakes in assigning phases to genes, especially when percent identity is remote from the alignment query. That's because GT and AG are common dinucleotides and sometimes multiple options seem viable (preserve reading frame). Of course, there's much more to splice sites than just two dinucleotides so sometimes those additional properties are used to sort out the possibilities (gene prediction software tools carry sophisticated versions of these rules). Usually just one possibility works consistently across the comparative genomics spectrum within a given orthology class of opsins.

It turns out that in post-lamprey deuterostomes not a single case of intron gain or loss can be documented in any of the 14 gene trees (recall each sequence set is maximally phylogenetically dispersed). Since each tree contains several billions of years of branch length, the overall event rate for opsins in this clade is lower than 1 per 50 billion years of evolutionary clock time. That's not atypical -- in fact intron gain and loss is know to be very infrequent (but not zero) across the entire vertebrate proteome.

However other issues must be considered such as alternative splicing, intron sliding, NAGNAG ambiguity, asymmetric relative frequencies of phase types, mechanisms and relative frequency of gains and loses, hotspots of predisposition, likelihood estimates of convergent evolution, migration out of GT-AG to minor splice forms and so forth. Alternative splicing is irrelevent to opsins because of their intolerant structure -- alternative transcripts in all likelihood are just the usual transcriptome noise. Intron sliding is a nutty literature concept repeatedly debunked. Acceptor ambiguity is real but not seen yet in opsins. Phase 0 is disproportionate genomewide, often half of all coding phases.

There is a general predisposition to enhanced intron loss distally (3') due to recombination with processed mrna; mechanisms of intron gain are a bit cryptic and -- like everything else -- cannot be assumed the same across all of Metazoa. General trends need not be applicable to this specific gene family, Hotspots may have relevance to opsins but apply to inaccessible ancestral sequence rather than contemporary forms.

Keeping all this in mind, I intronated nearly 200 phylogenetically dispersed opsins in the Opsin Classifier using direct genomic comparison when possible and homology annotation transfer when not. The error rate is not zero; anomalies needing revisiting are concentrated in 12 and 21 introns and in opsins without close homologs. When a gene model is fragmentary, only half the splice site may be available so that validation is lacking. In some assemblies, there seem to be sequencing errors that don't allow introns where they are required to avoid premature stop codons.

The literature on intron antiquity is hopelessly muddled due to intemperate speculation in the pre-informatics era of the previous century. Today we know that the vast majority of (say) human introns are very old, dating back to early unicellular eukaryotes (eg introns in human SUMF1 are shared with diatom). Consequently they were well entrenched at the time of Eumetazoan emergence and experienced little gain or loss in any but the rogue lineages (notably sea urchins, tunicates, nematodes, fruit flies). We expect most deuterostome introns to be present in at least some species of ecdysozoa, lophotrochozoa, and cnidaria; this has been validated recently in the case of Nematostella.

Let's consider first the intron situation in ciliary opsins and whether we can unambiguously determine the ancestral intron pattern at the time of Urbilatera or even Urmetazoa. We'll use common sense parsimony rather than maximal likelihood methods because these simply bury their subjectivity within rarely discussed model assumptions that aren't likely to consistently hold across this vast time and clade scale -- higher taxa sampling density on long branches is the best way to test and improve ancestral intron prediction.

Two detailed examples in Annotation Tricks section explain how the Opsin Classifier sequence collection can be used in conjunction with uBlast to determine whether exon breaks of a given opsin agree with another. Let's look now at the full set of all known ciliary opsins, knowing in advance that those in protostomes will ultimately arbitrate the deuterome situation as outgroup until such time as definitive relevently intronated cnidarian opsins are located.

It's apparent that all 109 deuterostome ciliary opsins in our current 10 orthology class collection (namely RHO1 RHO2 SWS2 SWS LWS PIN VAOP PPIN PARIE ENCEPH, with 4 classes RGR PER NEUR and MEL held out as intron pattern specificity controls) exhibit a single conserved intronation pattern across the human to echinoderm time scale. There are some significant events, all of which predate lamprey divergence, such as the extra intron in LWS opsins. Here the gene tree structure can provide outgroups capable of distinguishing intron gain from intron loss (LWS experienced a gain). This gene tree is reliably enough known from many publications or can be quickly generated with common software such as ClustalW from the vastly expanded collection in the Opsin Classifier.

In Lophotrochozoa, the situation is much more limited with just two Platynereis opsins, of which one is well-characterized by experiment and the other is directly intronatable. Perhaps with targeted sequencing effort, new cdna, additional bioinformatics, or more complete genomes, homologs will emerge in Capitella, Helobdella, Aplysia, Lottia, Schmidtea, or Schistosoma. These species already provide additional intronated opsins of melanopsin class.

In Ecdysozoa, 3 ciliary opsins had been previously established in Anopheles and Apis whereas they had been completely ruled out in the (truly finished) Drosophila genome. The list of genomic species with (the same) ciliary opsin can be readily extended to Culex, Aedes, Tribolium, Bombyx, and Daphnia. However gene loss seems to have happened repeatedly (or current coverage is insufficient; the gene cannot be found in Nasonia, Ixodes, and others.

(to be continued)