Bison: nuclear genomics: Difference between revisions

Tomemerald (talk | contribs) |

Tomemerald (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

=== The bison prion gene and species barrier to CWD === | === The bison prion gene and species barrier to CWD === | ||

The prion gene PRNP is one of the most intensively sequenced of all mammalian autosomal genes. Bison has independent sequences though none of these is geographically sourced at their GenBank entry or [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15477588,16033959 accompanying publications]. | The prion gene PRNP is one of the most intensively sequenced of all mammalian autosomal genes. Bison has three independent sequences though none of these is geographically sourced at their GenBank entry or [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15477588,16033959 accompanying publications]. The source of AY769958 is WGFD WBb0401, suggesting Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Wyoming Bison bison 0401 but that sequence is not further discussed (or even used) in [http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/content/full/86/8/2127 full text]. | ||

The bison PRNP gene overall is identical to those of its outgroups, yak, domestic cow, and water buffalo as befits a slowly evolving protein. However an interesting bison allele has been identified, namely M17T. This lies well within the signal peptide cleaved during maturation so | The bison PRNP gene overall is identical to those of its outgroups, yak, domestic cow, and water buffalo as befits a slowly evolving protein. However an interesting bison allele has been identified, namely M17T. This lies well within the signal peptide cleaved during maturation so would not appear in the final GPI-anchored protein on the exterior of the cytoplasmic membrane unless abnormally processed. | ||

Consequently this allele cannot influence the species barrier of bison to prion disease. The species barrier itself is difficult to predict but that of bison will be identical to cow. That risk comes from three sources: germline or somatic mutation in an individual, transmission from a public lands domestic sheep with scrapie, transmission from public lands mad cow, or transmission from deer, elk or moose affected with chronic wasting disease (scrapie that has previously crossed the cervid species barrier). | |||

Inherited prion disease is autosomal dominant with high | Inherited prion disease is autosomal dominant with high penetrence so does not revolve around inbreeding or high background frequency of disease alleles in a population (though late onset can bring about large pedigrees). It represents toxic gain of function, not loss of normal protein function which remains unknown despite 12,051 scientific studies as of 17 Feb 2011. | ||

The | The greatest single risk for inherited prion disease is amplification of the octapeptide repeat region PHGGGWGQ by replication slippage. Here bison have six octapeptide repeats, in the normal range but a risk factor for disease expansion. | ||

CpG hotspot mutations dominate the point mutation spectrum. | CpG hotspot mutations dominate the point mutation spectrum in mammals. The most common outcome for a CpG mutation is the purine transition CpA. Any of twelve amino acid substitutions can arise. When CpG resolves as the pyrimidine transition TpG, 8 non-synonymous outcomes are possible. | ||

Signal region indels are not especially rare among orthologs to the 4500-odd human genes with signal peptides of which 595 are experimentally validated, despite steric requirements of the binding pocket of the signal processing complex SRP. In actuality the distribution of signal peptide length is fairly broad. These indels can be rapidly screened in batches of 25 by Blat alignment relative to the 44 available vertebrate genomes. | Signal region indels are not especially rare among orthologs to the 4500-odd human genes with signal peptides of which 595 are experimentally validated, despite steric requirements of the binding pocket of the signal processing complex SRP. In actuality the distribution of signal peptide length is fairly broad. These indels can be rapidly screened in batches of 25 by Blat alignment relative to the 44 available vertebrate genomes. | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

http://proline.bic.nus.edu.sg/spdb/index.html | http://proline.bic.nus.edu.sg/spdb/index.html | ||

| Line 187: | Line 187: | ||

MGKIQLGYWILVLFIV<font color="red">T</font>WSDLGLCKKPKPRPG Trichosurus vulpecular</font> | MGKIQLGYWILVLFIV<font color="red">T</font>WSDLGLCKKPKPRPG Trichosurus vulpecular</font> | ||

Effect of CpG hotspot mutation on bison prion protein | |||

normal: 1 MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPGGGWNTGGSRYPGQGSPGGNRYPPQGGGGW 60 | |||

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSD+GLCKK+PKPGGGWNTGGS+YPGQGSPGGN YPPQGGGGW | |||

CpG CpA: 1 MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDMGLCKKQPKPGGGWNTGGSQYPGQGSPGGNHYPPQGGGGW 60 | |||

normal: 61 GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHGQWNKPSKPKTNM 120 | |||

GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTH QWNKPSKPKTNM | |||

CpG CpA: 61 GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHSQWNKPSKPKTNM 120 | |||

normal: 121 KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYEDRYYRENMHRYPNQVYYRPVDQY 180 | |||

KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYED YY ENMH YPNQVYYRPVDQY | |||

CpG CpA: 121 KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYEDHYYHENMHHYPNQVYYRPVDQY 180 | |||

normal: 181 SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTETDIKMMERVVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQRGASVIL 245 | |||

SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFT+TDIKMME+VVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQ+GASVIL | |||

CpG CpA: 181 SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTKTDIKMMEQVVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQQGASVIL 245 | |||

normal: 1 MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPGGGWNTGGSRYPGQGSPGGNRYPPQGGGGW 60 | |||

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKK PKPGGGWNTGGS YPGQGSPGGN YPPQGGGGW | |||

CpG TpG: 1 MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKK-PKPGGGWNTGGS-YPGQGSPGGNCYPPQGGGGW 58 | |||

normal: 61 GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHGQWNKPSKPKTNM 120 | |||

GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHGQWNKPSKPKTNM | |||

CpG TpG: 59 GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHGQWNKPSKPKTNM 118 | |||

normal: 121 KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYEDRYYRENMHRYPNQVYYRPVDQY 180 | |||

KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYED YY ENMH YPNQVYYRPVDQY | |||

CpG TpG: 119 KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYEDCYYCENMHCYPNQVYYRPVDQY 178 | |||

normal: 181 SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTETDIKMMERVVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQRGASVIL 245 | |||

SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTETDIKMME VVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQ GASVIL | |||

CpG TpG: 179 SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTETDIKMME-VVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQ-GASVIL 245 | |||

[[Category:Comparative Genomics]] | [[Category:Comparative Genomics]] | ||

Revision as of 14:33, 17 February 2011

Bison conservation genomics: introduction

The main nuclear genome of bison, like the mitochondrial genome, will have significant conservation management issues because the consequences of nineteenth and twentieth century bottlenecks (and consequent inbreeding) are still with us today.

Most conservation herds are derived from a tiny founding populations and maintained for many decades at far too low a population level, with surplus animals removed episodically without the slightest consideration of population genetic impacts. Other management practices such elimination of predators, winter feeding, gender imbalance, culling of unruly bulls, and trophy hunts also interfere with natural selection (survival of the fittest).

The founding individuals of a given herd -- even previously wild animals experiencing millenia of natural selection -- still have a substantial genetic load . Autosomal recessives form an important component of that load and are the primary focus here. These are gene mutations found in one of the two copies of non-sex chromosomes that are more or less masked by compensation by the properly functioning copy.

When the founding population is small, the gene frequency of an autosomal recessive mutation is necessarily high. As inbreeding is unavoidable, offspring can inherit two bad copies of the gene. In this homozygous state, no compensation can occur and the disease associated with the mutation is fully manifested. Note populations often harbor mutations at different sites in the same gene. Here the affected offspring can be a compound heterozygote -- two bad copies but at different sites in the same protein.

Looking just at same-site autosomal recessives, the two variables are the frequency q of the bad allele in the population and the coefficient of inbreeding f. The latter simply tallies the percentage of identical alleles by inherited descent (autozygosity). There is an assumption here that would not be valid for the YNP bison nineteenth century bottleneck, namely that the surviving parental animals were not already inbred.

This can be translated into millions of DNA base pairs lacking heterozygosity assuming a bison nuclear genome size of three billion. Then for f at 1/4, there 716,000,000 base pairs of inbreeding derived homozygosity, enough for 5,000 protein coding genes. This DNA will be somewhat broken up into blocks by recombination. For f at 1/8, these numbers are 358,000,000 bp and 2,500 genes. Other coefficients of inbreeding are quickly computed:

- Father/daughter, mother/son or brother/sister → 25%

- Grandfather/granddaughter or grandmother/grandson → 12.5%

- Half-brother/half-sister → 12.5%

- Uncle/niece or aunt/nephew → 12.5%

- Great-grandfather/great-granddaughter or great-grandmother/great-grandson → 6.25%

- Half-uncle/niece or half-aunt/nephew → 6.25%

- First cousins → 6.25%

- First cousins once removed or half-first cousins → 3.1%

- Second cousins or first cousins twice removed → 1.6%

- Second cousins once removed or half-second cousins → 0.78%

The frequency of an autosomal recessive disorder in the offspring of a consanguineous mating is then qf + qq (1-f). Inserting various coefficients of inbreeding and realistic values of deleterious alleles, it quickly emerges that almost all autosomal recessive disease in bison arises from inbreeding. Very rarely does it arise in the offspring of remotely related animals.

Example: suppose a bison bull is dominant for a few years. If it breeds with a calf it previously sired, f is 1/4. The odds that recessive disease did not result from inbreeding only exceed 50-50 when q exceeds 1/3. However q = 0.1 is the largest q known in human disease (hemochromatosis). Cystic fibrosis is another extreme case but there q is only 0.02. For a bison disease allele at that frequency, with a disease observed in the offspring, the odds are overwhelming (94%) that it came from inbreeding, not mating of unrelated bison representative of the whole populations. The odds are still high for the grandparent and first cousin situations (88% and 77%) and are higher still for lower q that are more typical. In summary, autosomal recessive disease in bison can be brought back to natural levels simply by avoidance of inbreeding.

Extensive whole genome sequencing in humans has established that each individual human carries 275 loss-of-function variants and 75 variants previously implicated in inherited disease (both classes typically heterozygous and differing from person to person), additionally varying from the reference human proteome of 9,000,000 amino acids at 10,500 other sites (0.12%). The deleterious alleles include 200 in-frame indels, 90 premature stop codons, 45 splice-site-disrupting variants and 235 deletions shifting reading frame.

In bison the overall genetic load will surely be worse in view of extreme bottlenecks, small herd size history and unavoidable inbreeding. Offspring with deleterious nuclear genes in the homozygous state will be more abundant than in humans who are inbred too but not nearly to the same extent.

Measuring incest in bison

Little bison nuclear genome data is currently available but that situation is changing rapidly with ongoing whole genome sequencing projects not only for bison but also of closely related species such as yak, water buffalo, domestic cow and fossil steppe and plains bison that can help establish a baseline of normality for current conservation herd bison.

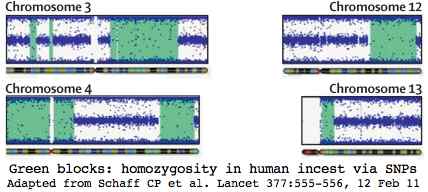

Humans however are already intensively studied. Here incest studies in human have transferable implications to bison herds with limited a number of bulls or a single bull maintaining breeding dominance across generations. The graphic at left shows how a human SNP chip detected incest in a 3-year-old boy with multiple medical issues without access to parental dna.

The green blocks show 668 million base pairs of DNA homozygosity out of the 716 Mbp expected for parent-child incest (coefficient of inbreeding 1/4, human genome size 3.000 Mbp). This represents a quarter of the genes, so approximately 5,000 of which 62 would be expected to have carried deleterious mutations. Some 31 on average would now be homozygous deleterious in the child.

Humans exiting Africa experienced significant bottlenecks then and during subsequent glaciations and climate change as well as founding population migrations. Inbreeding was unavoidable at times. Cousin marriage remains very common today in human populations, with some long been closed to outsiders and now rife with autosomal recessive disease. Thus there is considerable applicability of human data to the bison situation.

The diagram below shows genealogical terminology relative to inbreeding. It is important to track gender because X-linked mutations manifest themselves readily in males (because the X chromosome there is single copy). Additionally, the mitochondrial genome is maternally inherited and the two genomes need to be co-managed. The Y chromosome is also of interest because its non-recombining portion in bison-cow hybrid herds would still be intact (initial crosses always used a bison bull).

Incest is a crime in nearly all human societies but management-driven incest in bison is not. The SNP chip here had 620,901 markers, representing 12x the resolution available for the comparable cattle chip applied to bison. Thus the bison chip would give clear results but not the sharp resolution because the median marker spacing would slip to 32.4 kbp and the average spacing to 56.4 kbp. For matings between bison related at the second degree (uncle-niece, double first cousins), the inbreeding coefficient is 1/8 and expected level of homozygosity 358 Mb. Here the calf would carry roughly 15 deleterious mutations.

Bison are routinely corralled and tested for previous exposure to brucellosis. The blood samples taken also serve for DNA sampling, where a tiny volume placed on special filter paper would be stable for years at room temperature. These FTA cards provide DNA suitable for readout on the widely used bovine SNP Illumina beadchip. Thus it is fast and cheap to determine the extent of inbreeding at Yellowstone National Park even though cattle introgression (the original use of the chip in bison) is not the issue there. Inbreeding and long-ago introgression are just opposite extremes.

Actual opportunistic measurement of corralled, radio-collared, or naturally expired animals is vastly preferable to academic exercises in theoretic population modeling. There is no real interest in maintenance of neutral allele frequencies measured by microsatellites or junk DNA SNPs but rather in consequential frequencies of deleterious alleles in specific genes that are the legacy of the initial bottleneck, as well as adaptive alleles. The genes and alleles of interest have only been determined so far for bison mitochondria.

Real bison herds are impossibly complex. The females are strongly matrilocal. Although distinct herds may persist for decades because of physical barriers between valleys, bulls and sometimes family groups of cows may wander between them. The herd sizes and composition fluctuate dramatically from year to year depending primarily on the severity of culls, its targeting to extended family groups, snowfall in winter, and susceptibility to predation and disease.

One wonders what management purpose the obscure theoretical constructs of population ecology can serve in real world conservation genomics, given real bison herds have constantly shifting and essentially unmeasurable hereditary allele parameters in 20,000 genes, with two weakly related bison differing at more than 10,500 amino acid sites.

Microsatellites are worthless for conservation genomics

(to be continued)

Results to date from the bovine SNP chip

(to be continued)

The bison prion gene and species barrier to CWD

The prion gene PRNP is one of the most intensively sequenced of all mammalian autosomal genes. Bison has three independent sequences though none of these is geographically sourced at their GenBank entry or accompanying publications. The source of AY769958 is WGFD WBb0401, suggesting Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Wyoming Bison bison 0401 but that sequence is not further discussed (or even used) in full text.

The bison PRNP gene overall is identical to those of its outgroups, yak, domestic cow, and water buffalo as befits a slowly evolving protein. However an interesting bison allele has been identified, namely M17T. This lies well within the signal peptide cleaved during maturation so would not appear in the final GPI-anchored protein on the exterior of the cytoplasmic membrane unless abnormally processed.

Consequently this allele cannot influence the species barrier of bison to prion disease. The species barrier itself is difficult to predict but that of bison will be identical to cow. That risk comes from three sources: germline or somatic mutation in an individual, transmission from a public lands domestic sheep with scrapie, transmission from public lands mad cow, or transmission from deer, elk or moose affected with chronic wasting disease (scrapie that has previously crossed the cervid species barrier).

Inherited prion disease is autosomal dominant with high penetrence so does not revolve around inbreeding or high background frequency of disease alleles in a population (though late onset can bring about large pedigrees). It represents toxic gain of function, not loss of normal protein function which remains unknown despite 12,051 scientific studies as of 17 Feb 2011.

The greatest single risk for inherited prion disease is amplification of the octapeptide repeat region PHGGGWGQ by replication slippage. Here bison have six octapeptide repeats, in the normal range but a risk factor for disease expansion.

CpG hotspot mutations dominate the point mutation spectrum in mammals. The most common outcome for a CpG mutation is the purine transition CpA. Any of twelve amino acid substitutions can arise. When CpG resolves as the pyrimidine transition TpG, 8 non-synonymous outcomes are possible.

Signal region indels are not especially rare among orthologs to the 4500-odd human genes with signal peptides of which 595 are experimentally validated, despite steric requirements of the binding pocket of the signal processing complex SRP. In actuality the distribution of signal peptide length is fairly broad. These indels can be rapidly screened in batches of 25 by Blat alignment relative to the 44 available vertebrate genomes.

However few of these indels have any phylogenetic depth. It does not appear that the PRNP indel in euarchontoglires has any significant effect on cell targeting by the signal peptide (or subsequent membrane topology). It is not that indels in signal peptides are so rare but rather narrowly windowed basal events in large clades. http://proline.bic.nus.edu.sg/spdb/index.html

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Bison bison CR227All1 AY769958

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Bison bison CR227All2

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Bison bonasus

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Bos taurus

MVKRHIGSWILVLFVVMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Bubalus bubalis

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVVMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Syncerus caffer

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Rangifer tarandus

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Alces alces

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Capreolus capreolus

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Kobus megaceros

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Connochaetes taurinus

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Ammotragus lervia

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Hippotragus niger

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Capris hircus

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Cervus elaphus

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Cervus elaphus nelsoni

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Dama dama

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Odocoileus virginianus

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVALCKKRPKPG Oryx leucoryx

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Ovibos moschatus

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Ovis aries

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Ovis canadensis

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVALCKKRPKPG Tragelaphus strepsiceros

MVKSHIGGWILVLFVAAWSDIGLCKKRPKPG Sus scrofa

MVKSHMGSWILVLFVVTWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Camelus dromedarius

MVKSHMGSWILVLFVVTWSDMGLCKKRPKPG Vicugna vicugna

MVKSLVGGWILLLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Myotis lucifugus

MVKNYIGGWILVLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Pteropus vampyrus

MVKSHIANWILVLFVATWSDMGFCKKRPKPG Tursiops truncatus

MVKSHIGGWILLLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Canis lupus familiaris

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Felis catus

MVKSHIGSWLLVLFVATWSDIGFCKKRPKPG Mustela putorius

MVKSHIGSWLLVLFVATWSDIGFCKKRPKPG Mustela vison

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Ailuropoda melanoleuca

MVKSHVGGWILVLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Equus caballus

MVRSHVGGWILVLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Diceros bicornis

MVKNHVGCWLLVLFVATWSEVGLCKKRPKPG Erinaceus europaeus

MVTGHLGCWLLVLFMATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Sorex araneus

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Homo sapiens

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Pan troglodytes

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Gorilla gorilla

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Pongo pygmaeus

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Nomascus leucogenys

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Hylobates lar

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Symphalangus syndactylus

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Macaca arctoides

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Macaca fascicularis

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Macaca fuscata

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Macaca mulatta

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Macaca nemestrina

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Papio hamadryas

MA--NLGCWMLFLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Callithrix jacchus

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Cebus apella

MA--NLGCWMLVVFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Cercopithecus aethiops

MA--NLGCWMLVVFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Cercopithecus dianae

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Colobus guereza

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Presbytis francoisi

MA--NLGCWMLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRPKPG Saimiri sciureus

MA--KLGYWLLVLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Tarsius syrichta

MA--NLGCWMLVVFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Microcebus murinus

MA--RLGCWMLVLFVATWSDIGLCKKRPKPG Otolemur garnettii

ME--NLGCWMLILFVATWSDIGLCKKRPKPG Cynocephalus variegatus

MA--QLGCWLMVLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Tupaia belangeri

MA--NLGYWLLALFVTMWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Mus musculus

MA--NLGYWLLALFVTTCTDVGLCKKRPKPG Rattus norvegicus

MA--NLGYWLLALFVTTCTDVGLCKKRPKPG Rattus rattus

MA--NAGCWLLVLFVATWSDTGLCKKRPKPG Cavia porcellus

MA--NLGYWLLALFVTTWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Apodemus sylvaticus

MA--NLGCWLLVLFVATWSDLGLCKKRTKPG Dipodomys ordii

MA--NLSYWLLAFFVTTWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Clethrionomys glareolus

MA--NLSYWLLALFVATWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Cricetulus griseus

MA--NLSYWLLALFVATWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Cricetulus migratorius

MA--NLGYWLLALFVTMWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Meriones unguiculatus

MA--NLSYWLLALFVAMWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Mesocricetus auratus

MA--NLGYWLLALFVATWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Sigmodon fulviventer

MA--NLGYWLLALFVATWTDVGLCKKRPKPG Sigmodon hispiedis

MV--NPGCWLLVLFVATLSDVGLCKKRPKPG Spermophilus tridecemlineatus

MV--NPGYWLLVLFVATLSDVGLCKKRPKPG Sciurus vulgaris

MA--HLGYWMLLLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Oryctolagus cuniculus

MA--HLSYWLLVLFVAAWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Ochotona princeps

MVKSHLGCWIMVLFVATWSEVGLCKKRPKPG Cyclopes didactylus

MVRSRVGCWLLLLFVATWSELGLCKKRPKPG Dasypus novemcinctus

MVKGTVSCWLLVLVVAACSDMGLCKKRPKPG Echinops telfairi

MVKSSLGCWILVLFVATWSDMGLCKKRPKPG Elephas maximus

MVKSSLGCWILVLFVATWSDMGLCKKRPKPG Loxodonta africana

MVKSSLGCWMLVLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Procavia capensis

MMKSGLGCWILVLFVATWSDVGLCKKRPKPG Orycteropus afer

MVKSGLGCWILVLFVATWSDVGVCKKRPKPG Trichechus manatus

MAKIQLGYWILALFIVTWSELGLCKKPKTRPG Macropus eugenii

MGKIHLGYWFLALFIMTWSDLTLCKKPKPRPG Monodelphis domestica

MGKIQLGYWILVLFIVTWSDLGLCKKPKPRPG Trichosurus vulpecular

Effect of CpG hotspot mutation on bison prion protein

normal: 1 MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPGGGWNTGGSRYPGQGSPGGNRYPPQGGGGW 60

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSD+GLCKK+PKPGGGWNTGGS+YPGQGSPGGN YPPQGGGGW

CpG CpA: 1 MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDMGLCKKQPKPGGGWNTGGSQYPGQGSPGGNHYPPQGGGGW 60

normal: 61 GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHGQWNKPSKPKTNM 120

GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTH QWNKPSKPKTNM

CpG CpA: 61 GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHSQWNKPSKPKTNM 120

normal: 121 KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYEDRYYRENMHRYPNQVYYRPVDQY 180

KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYED YY ENMH YPNQVYYRPVDQY

CpG CpA: 121 KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYEDHYYHENMHHYPNQVYYRPVDQY 180

normal: 181 SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTETDIKMMERVVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQRGASVIL 245

SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFT+TDIKMME+VVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQ+GASVIL

CpG CpA: 181 SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTKTDIKMMEQVVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQQGASVIL 245

normal: 1 MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKKRPKPGGGWNTGGSRYPGQGSPGGNRYPPQGGGGW 60

MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKK PKPGGGWNTGGS YPGQGSPGGN YPPQGGGGW

CpG TpG: 1 MVKSHIGSWILVLFVAMWSDVGLCKK-PKPGGGWNTGGS-YPGQGSPGGNCYPPQGGGGW 58

normal: 61 GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHGQWNKPSKPKTNM 120

GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHGQWNKPSKPKTNM

CpG TpG: 59 GQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGGTHGQWNKPSKPKTNM 118

normal: 121 KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYEDRYYRENMHRYPNQVYYRPVDQY 180

KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYED YY ENMH YPNQVYYRPVDQY

CpG TpG: 119 KHVAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPLIHFGSDYEDCYYCENMHCYPNQVYYRPVDQY 178

normal: 181 SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTETDIKMMERVVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQRGASVIL 245

SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTETDIKMME VVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQ GASVIL

CpG TpG: 179 SNQNNFVHDCVNITVKEHTVTTTTKGENFTETDIKMME-VVEQMCITQYQRESQAYYQ-GASVIL 245