USH2A SNPs

USH2A

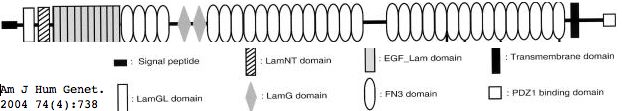

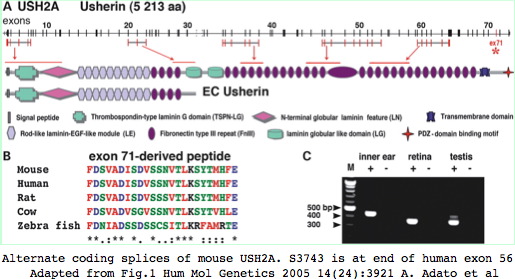

Usherin (USH2A), a 71-exon coding gene located on human chromosome 1q41], encodes a 5202 residue multi-domain protein comprised of a signal peptide, a PDZ1 binding domain (for USH1C and WHRN), 1 laminin NT-terminal domain, 10 laminin EGF-like domains, 4 fibronectin type-III domains (for collagen IV and fibronectin), and 2 laminin G-like domains followed by 31 additional fibronectin type-III domains all tethered to the cytoplasmic exterior by a single transmembrane domain.

The usherin gene is expressed in the basement membrane of many (but not all) cell types, notably in ear interstereocilia ankles and below retinal pigment epithelial cells (Bruch's layer) and indeed in ciliary photoreceptor cells themselves. When normal function is disrupted by mutations in both copies, non-vestibular sensorineural deafness and degeneration of retinal photoreceptor cells called Usher syndrome type IIA results.

In Usher Syndrome 2A, children are born hard-of-hearing, able to detect lower tones better than higher frequencies. Only 10 dB of further loss occurs the next several decades. Mid-periferal vision loss (of rods) has much later onset but can be compensated for eye scanning utilizing healthy parts of the retina (where acuity can still be 20/20). The field of vision narrows considerably over time but can still be compensatable.

Initially, only the first 21 of 71 exons were studied but later it emerged that the gene was much longer and exquisitly sensitive to certain point mutations along the entire length of the protein, all leading -- in the homozygous or compound state -- to essentially the same disease: 125, 163, 230, 268, 303, 334, 346, 352, 478, 536, 595, 644, 713, 759, 1212, 1349, 1486, 1572, 1665, 1757, 2080, 2086, 2106, 2169, 2238, 2265, 2266, 2292, 2562, 2875, 2886, 3088, 3099, 3115, 3124, 3144, 3199, 3411, 3504, 3521, 3590, 3835, 3868, 3893, 4054, 4115, 4232, 4433, 4439, 4487, 4592, 4624, 4795, 5031.

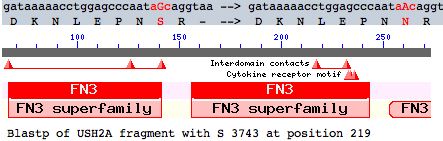

Many other coding variations are known (non-synonymous SNPs). This article evaluates a particular new SNP in USH2A using comparative genomics but the methods here are applicable to any coding variation. This mutation occurs as a non-hotspot G-->A transition causing a seemingly innoculous S-->N amino acid change at postion 3743. This is just downstream from a glycosylation motif and very near known FN3 interdomain contact residues and a cytokine receptor motif (according to its annotation at SwissProt). This residue lies at a conserved turn initiating the seventh beta strand in the 22nd fibronectin domain which is split across exon 56 and 57.

This change will be shown significant (not plausibly neutral). It could represent an adaptive innovation but is more likely deleterious. The gene is single-copy so there are no prospects for compensation by a second gene. Consequently the mutation, if present on both alleles, could well result in a new form of Usher syndrome type IIA.

Background

USH2A, while resembling just another domain scramble, actually traces back to pre-blaterans in a coherent manner. Nearly full-length ortholog candidates can readily be recovered from sea anemone and hydra. Despite good representation in cnidarians (where its normal function may be similar), the gene seems completely lost (or majjorly diverged) from all arthropods and lophotrochozoans. It's not clear whether the need for a basement membrane organizer has been lost or whether some other gene has taken over USH2A's role in these clades.

Focusing now on the fibronectin FN3 domains (that envelop S3743), these are an ancient and exceedingly common domain in bilaterans with 2% of the human proteome containing them (400 genes), often in multiple tandem copies having a role in cell adhesion. However they are not particularly well conserved in primary sequence, though the tertiary structure likely holds up well enough for the structure at residue 3743 to be determined with both serine and asparagine present.

Here the best blastp match elsewhere within the human proteome to the FN3 domain containg residue 3743 is a fibronectin domain of PTPRQ, a dimly related protein tyrosine phosphatase with merely 28% of the fibronectin residues matching.

Internally, the best match to the other 30 FN3 domains of USH2A is not noticably better, suggesting very substantial divergence since these domains duplicated from a common source (either as internal tandems or domain shuffles). If as suggested above, USH2A had already assumed its contemporary domain structure in pre-bilateran metazoa, ample time has passed to produce the observed divergences between the individual domains.

While comparative genomics of intron positions and phases in a 71-exon protein are tedious to curationally pursue, the fibronectin domain containing S3743 falls across parts of three exons, whose phases are 12 and 21. This suggests that subsequent to the ancient intronation era, simple internal tandem duplications might not result in either a coherent reading phase or domain. Thus the domain structure of USH2A, while appearing somewhat arbitrary in its FN3 multiplicities, actually may be quite constrained by intronation against both contraction or expansion (in addition to whatever individual functional domain constrains exist).

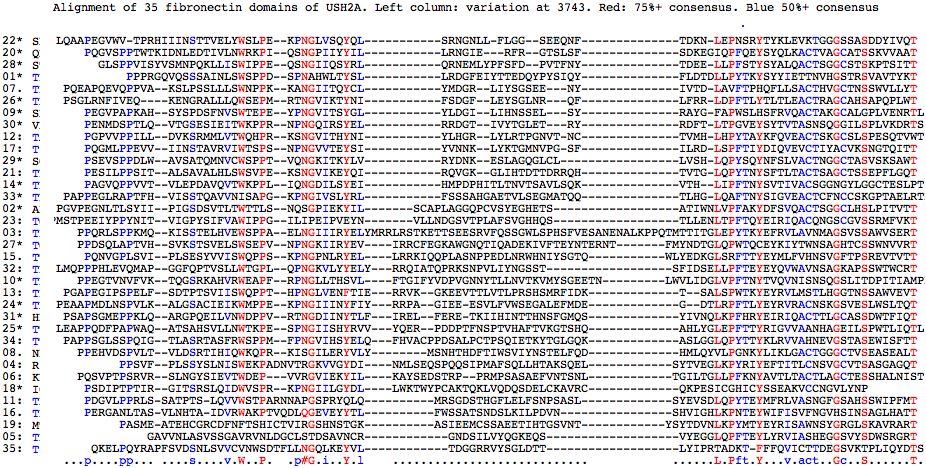

As can be seen below, the internal fibronectin repeats are most often T threonine at the position corresponding to S3743 though other residues, not including the asparagine of S3743N, also occur. Here the numbering of better matches within the full length protein indicates they do not always correspond in match quality order to the linear order of the FN3 repeat within the protein.

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

FBN.. 3702 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGN-LLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

WS+PEK NG++ +YQ+ + G L+ ++ + T L+P +

FBN.. 3610 WSVPEKSNGVIKEYQIRQVGKGLIHTDTTDRRQHTVTGLQPYT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLL-FLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

W PE+ NG++ Y+L RN L F N+TD+ L P S

FBN.. 4285 WIPPEQSNGIIQSYRLQRNEMLYPFSFDPVTFNYTDEELLPFS

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

W P K NG+++ Y + +G L N T +L P +

FBN.. 2553 WQHPRKSNGVITHYNIYLHGRLYLRTPGNVTNCTVMHLHPYT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

W P PNG + Y+L R+G +++ G E + D L P

FBN.. 4464 WKPPRNPNGQIRSYELRRDGTIVYTG--LETRYRDFTLTPGV

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

W+ P+K NG+++QY L +G L++ G E+N+T +L +

FBN.. 2075 WNPPKKANGIITQYCLYMDGRLIYSG--SEENYTVTDLAVFT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKN-LEPNS

W P + NG + Y L RNG F G S +F+DK ++P

FBN.. 3521 WRKPIQSNGPIIYYILLRNGIERFRGTS--LSFSDKEGIQPFQ

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

W+ P PNG+V++Y + N L G + +F ++L P +

FBN.. 3040 WTSPSNPNGVVTEYSIYVNNKLYKTGMNVPGSFILRDLSPFT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRN-------GNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKN--LEPNS

W P PNGLV + + R L+ L S F DK L P +

FBN.. 2644 WQPPTHPNGLVENFTIERRVKGKEEVTTLVTLPRSHSMRFIDKTSALSPWT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

WS P + NG++ Y + +G L + G + + F + L+P +

FBN.. 4087 WSEPMRTNGVIKTYNIFSDGFLEYSGLNRQ--FLFRRLDPFT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEE----QNFTDKNLEPNS

WS P+ PN Y L R+G ++ + Q F D +L P +

FBN.. 1074 WSPPDSPNAHWLTYSLLRDGFEIYTTEDQYPYSIQYFLDTDLLPYT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNG------NLLFLGGSEEQNFTDK--NLEPNS

W PEKPNG++ Y + R ++LF+ F D+ L P +

FBN.. 3887 WMPPEKPNGIIINYFIYRRPAGIEEESVLFVWSEGALEFMDEGDTLRPFT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

WS P NG +++Y L R N L G + +L+P S

FBN.. 4376 WSPPTVQNGKITKY-LVRYDNKESLAG-QGLCLLVSHLQPYS

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQL--------SRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNS

W+ P +PNG V Y+L R N + + +F D L P +

FBN.. 4657 WTGPLQPNGKVLYYELYRRQIATQPRKSNPVLIYNGSSTSFIDSELLPFT

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQL------SRNGNLLFLGGSEE----QNFTDKNLEPNS

W P + NG + Y L R ++ + + Q++ L+P

FBN.. 4552 WDPPVRTNGDIINYTLFIRELFERETKIIHINTTHNSFGMQSYIVNQLKPFH

FBN22 1 WSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRN-------GN--------LLFLGGSEEQN---FTDKNLEPNS 42

WS P PNG + +Y++ R GN ++F + E+N + D L+P +

FBN.. 4175 WSEPVNPNGKIIRYEVIRRCFEGKAWGNQTIQADEKIVFTEYNTERNTFMYNDTGLQPWT 4234

Pseudogene issues

Long isoform USH2A transcripts are over 15,000 bp in length. Consequently position 3743 is not even represented in the set of all human direct transcripts. Even should a retrogene arise from retropositioing, it is unlikely that the process would extent upstream so many exons. Unsurprisingly no processed pseudogenes are evident in any mammalian genome (tblastn of wgs division of GenBank). Thus no potential for confusion exists in locating orthologs of USH2A even in distant species with incomplete genomes.

Paralog issues

No close paralog exists in the human proteome according to the UCSC GeneSorter track. The nearest matches are to other proteins containing laminin or fibronectin domains. No potential for confusion with other genes exists within vertebrates; however comparative genomics at and before teleost fish divergence needs more careful treatment because of whole genome and domain expansion.

Tandem domain repeat issues

In proteins with multiple copies of a given domain, both expansion and contraction can occur over evolutionary timescales resulting in different numbers of repeats in different clades. Under these circumstances it can be difficult to establish orthologs of a given domain. However here the fibronectin domains diverged early on and the 22nd domain seems to be present in all vertebrates with genome projects as a single-copy domain (meaning here no recent duplications or losses).

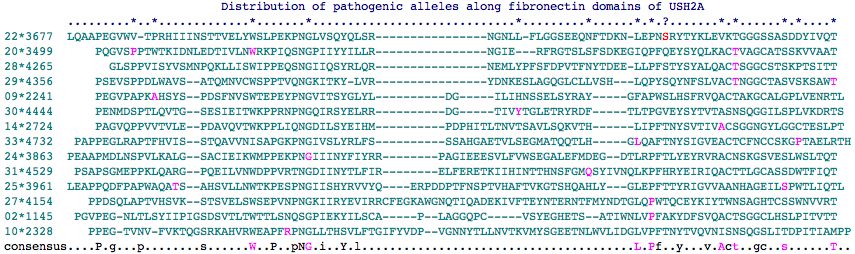

The alignment of fibronectin domains in human USH2A shows pockets of conservation (notably LEPNSRY about S3743 in the 22nd FN3 domain) and certain conserved anchor residues but on the whole is mediocre due to gaps necessitated by length differences. The second alignment -- just of FN3 domains contained verified pathogenic mutationv -- shows these sites are highly correlated with conserved residues (8 of 24 are represented, two sites multiple times in separate FN3 domains). Possibly some of the best conserved sites cannot be mutated without much more far-reaching effects on all tissues in which USH2A is expressed.

Analysis of the full set fibronectin domains somewhat strengthens the case for S3743N pathogenicity (it lies in a conserved patch with two nearby sites proven pathogenic and similar hydroxyl T is most abundant residue here and in deeper phylogeny) but not overwhelmingly (the 8th domain has N at homologous position).

Some scepticism is in order for pathogenicity of Y4487C and Q4592H in the 30th and 31st FN3 domains in view of their position in apparently unconstrained loop positions with no observed interdomain conservation. Yet tblastn of both at GenBank wgs shows remarkable phylogenetic conservation (data not shown) within each individual repeat, similar to domain 22. This could be pursued for the other positions falling outside the conserved and semi-conserved residues characterizing fibronectins.

The issue here is disentangling universal from individual fibronectin conservation issues. The effect of interchanging order of domains, like that of deleting or adding domains, has not been studied. Substitutability of genes across species (human for sea anemone?) would help define the rigidity of FN3 subunit requirements.

What is needed here online alignment software that accept a fasta sequence array (in effect a simple relational db) and outputs something whose rows are individual Logos. More simply, it could use a faster header naming scheme to collapse a conventional alignment to the index species. Many human genes have internally repeated domains and many others have full-length paralogs (which can be treated like tandem repeats). Evaluating coding SNPs is a huge issue in genomic medicine and even slight improvements in forecasting could have significant benefits.

Fasta sequences for the 35 fibronectin domains of USH2A are shown below (as delineated at SwissProt]). Those containing a mutation known to give rise to USH2A Syndrome contain * in their header -- some are found in patients but are of uncertain pathogenicity. The mutation itself is flanked by spaces in the fasta sequence itself for readability. There are 22 known sites in 18 different fibronectin domains according to this analysis. Note still other pathogenic mutations occur interstitially (between FN3 domains).

>01*1058-1143 86aa P1059L uncertain pathogenicity P P PRGQVQSSSAINLSWSPPDSPNAHWLTYSLLRDGFEIYTTEDQYPYSIQYFLDTDLLPYTKYSYYIETTNVHGSTRSVAVTYKT >02*1145-1238 94aa P1212L PGVPEGNLTLSYIIPIGSDSVTLTWTTLSNQSGPIEKYILSCAPLAGGQPCVSYEGHETSATIWNLV P FAKYDFSVQACTSGGCLHSLPITVTT >03:1242-1357 116aa PPQRLSPPKMQKISSTELHVEWSPPAELNGIIIRYELYMRRLRSTKETTSEESRVFQSSGWLSPHSFVESANENALKPPQTMTTITGLEPYTKYEFRVLAVNMAGSVSSAWVSERT >04:1367-1462 96aa PPSVFPLSSYSLNISWEKPADNVTRGKVVGYDINMLSEQSPQQSIPMAFSQLLHTAKSQELSYTVEGLKPYRIYEFTITLCNSVGCVTSASGAGQT >05:1871-1949 79aa GAVVNLASVSSGAVRVNLDGCLSTDSAVNCRGNDSILVYQGKEQSVYEGGLQPFTEYLYRVIASHEGGSVYSDWSRGRT >06:1954-2051 98aa PQSVPTPSRVRSLNGYSIEVTWDEPVVRGVIEKYILKAYSEDSTRPPRMPSASAEFVNTSNLTGILTGLLPFKNYAVTLTACTLAGCTESSHALNIST >07.2052-2138 87aa PQEAPQEVQPPVAKSLPSSLLLSWNPPKKANGIITQYCLYMDGRLIYSGSEENYIVTDLAVFTPHQFLLSACTHVGCTNSSWVLLYT >08.2142-2236 95aa PPEHVDSPVLTVLDSRTIHIQWKQPRKISGILERYVLYMSNHTHDFTIWSVIYNSTELFQDHMLQYVLPGNKYLIKLGACTGGGCTVSEASEALT >09*2241-2325 85aa A2249D PEGVPAPK A HSYSPDSFNVSWTEPEYPNGVITSYGLYLDGILIHNSSELSYRAYGFAPWSLHSFRVQACTAKGCALGPLVENRTL >10*2328-2432 105aa R2354H PPEGTVNVFVKTQGSRKAHVRWEAPF R PNGLLTHSVLFTGIFYVDPVGNNYTLLNVTKVMYSGEETNLWVLIDGLVPFTNYTVQVNISNSQGSLITDPITIAMPP >11:2435-2528 94aa PDGVLPPRLSSATPTSLQVVWSTPARNNAPGSPRYQLQMRSGDSTHGFLELFSNPSASLSYEVSDLQPYTEYMFRLVASNGFGSAHSSWIPFMT >12:2533-2619 87aa PGPVVPPILLDVKSRMMLVTWQHPRKSNGVITHYNIYLHGRLYLRTPGNVTNCTVMHLHPYTAYKFQVEACTSKGCSLSPESQTVWT >13:2621-2718 98aa PGAPEGIPSPELFSDTPTSVIISWQPPTHPNGLVENFTIERRVKGKEEVTTLVTLPRSHSMRFIDKTSALSPWTKYEYRVLMSTLHGGTNSSAWVEVT >14*2724-2812 89aa A2795S PAGVQPPVVTVLEPDAVQVTWKPPLIQNGDILSYEIHMPDPHITLTNVTSAVLSQKVTHLIPFTNYSVTIV A CSGGNGYLGGCTESLPT >15.2821-2920 100aa PQNVGPLSVIPLSESYVVISWQPPSKPNGPNLRYELLRRKIQQPLASNPPEDLNRWHNIYSGTQWLYEDKGLSRFTTYEYMLFVHNSVGFTPSREVTVTT >16.2925-3015 91aa PERGANLTASVLNHTAIDVRWAKPTVQDLQGEVEYYTLFWSSATSNDSLKILPDVNSHVIGHLKPNTEYWIFISVFNGVHSINSAGLHATT >17:3020-3105 86aa PQGMLPPEVVIINSTAVRVIWTSPSNPNGVVTEYSIYVNNKLYKTGMNVPGSFILRDLSPFTIYDIQVEVCTIYACVKSNGTQITT >18*3110-3200 91aa R3124G uncertain pathogenicity PSDIPTPTIRGITS R SLQIDWVSPRKPNGIILGYDLLWKTWYPCAKTQKLVQDQSDELCKAVRCQKPESICGHICYSSEAKVCCNGVLYNP >19:3404-3494 91aa PASMEATEHCGRCDFNFTSHICTVIRGSHNSTGKASIEEMCSSAEETIHTGSVNTYSYTDVNLKPYMTYEYRISAWNSYGRGLSKAVRART >20*3499-3585 87aa P3504T W3521R T3571M PQGVS P PTWTKIDNLEDTIVLN W RKPIQSNGPIIYYILLRNGIERFRGTSLSFSDKEGIQPFQEYSYQLKAC T VAGCATSSKVVAAT >21:3590-3676 87aa PESILPPSITALSAVALHLSWSVPEKSNGVIKEYQIRQVGKGLIHTDTTDRRQHTVTGLQPYTNYSFTLTACTSAGCTSSEPFLGQT >22*3677-3767 91aa S3743N uncertain pathogenicity LQAAPEGVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPN S RYTYKLEVKTGGGSSASDDYIVQT >23:3768-3862 95aa PMSTPEEIYPPYNITVIGPYSIFVAWIPPGILIPEIPVEYNVLLNDGSVTPLAFSVGHHQSTLLENLTPFTQYEIRIQACQNGSCGVSSRMFVKT >24*3863-3960 98aa G3895E PEAAPMDLNSPVLKALGSACIEIKWMPPEKPN G IIINYFIYRRPAGIEEESVLFVWSEGALEFMDEGDTLRPFTLYEYRVRACNSKGSVESLWSLTQT >25*3961-4062 102aa T3976M S4054I LEAPPQDFPAPWAQA T SAHSVLLNWTKPESPNGIISHYRVVYQERPDDPTFNSPTVHAFTVKGTSHQAHLYGLEPFTTYRIGVVAANHAGEIL S PWTLIQTL >26*4066-4150 85aa R4115C uncertain pathogenicity PSGLRNFIVEQKENGRALLLQWSEPMRTNGVIKTYNIFSDGFLEYSGLN R QFLFRRLDPFTLYTLTLEACTRAGCAHSAPQPLWT >27*4154-4258 105aa P4232R PPDSQLAPTVHSVKSTSVELSWSEPVNPNGKIIRYEVIRRCFEGKAWGNQTIQADEKIVFTEYNTERNTFMYNDTGLQ P WTQCEYKIYTWNSAGHTCSSWNVVRT >28*4265-4351 87aa T4337M GLSPPVISYVSMNPQKLLISWIPPEQSNGIIQSYRLQRNEMLYPFSFDPVTFNYTDEELLPFSTYSYALQAC T SGGCSTSKPTSITT >29*4356-4439 84aa T4425M T4439I PSEVSPPDLWAVSATQMNVCWSPPTVQNGKITKYLVRYDNKESLAGQGLCLLVSHLQPYSQYNFSLVAC T NGGCTASVSKSAW T >30*4444-4528 85aa Y4487C PENMDSPTLQVTGSESIEITWKPPRNPNGQIRSYELRRDGTIV Y TGLETRYRDFTLTPGVEYSYTVTASNSQGGILSPLVKDRTS >31*4529-4627 99aa Q4592H PSAPSGMEPPKLQARGPQEILVNWDPPVRTNGDIINYTLFIRELFERETKIIHINTTHNSFGM Q SYIVNQLKPFHRYEIRIQACTTLGCASSDWTFIQT >32:4633-4730 98aa LMQPPPHLEVQMAPGGFQPTVSLLWTGPLQPNGKVLYYELYRRQIATQPRKSNPVLIYNGSSTSFIDSELLPFTEYEYQVWAVNSAGKAPSSWTWCRT >33*4732-4825 94aa L4795R P4818L PAPPEGLRAPTFHVISSTQAVVNISAPGKPNGIVSLYRLFSSSAHGAETVLSEGMATQQTLHG L QAFTNYSIGVEACTCFNCCSKG P TAELRTH >34:4826-4927 102aa PAPPSGLSSPQIGTLASRTASFRWSPPMFPNGVIHSYELQFHVACPPDSALPCTPSQIETKYTGLGQKASLGGLQPYTTYKLRVVAHNEVGSTASEWISFTT >35:4928-5014 87aa QKELPQYRAPFSVDSNLSVVCVNWSDTFLLNGQLKEYVLTDGGRRVYSGLDTTLYIPRTADKTFFFQVICTTDEGSVKTPLIQYDTS

Known splice variations

With over 15,000 bp needed for an mRNA encoding full length gene yet typical cDNA reads of 600 bp, more than 25 reads are required simply to tile the gene once. However reads tend to pile up at termini so realistically several hundred transcripts would be needed in each of several species to establish splice variants with any phylogenetic depth.

A great many human alternative splices are evidently transcript noise resulting in non-functional protein (as is clear from 7-transmembrane GPCR examples which are necessarily dysfunctional). It's difficult to understand how USH2A could be so exquisitely sensitive to (sometimes quite mild) point mutations along its entire length yet still function after large deletions wipe out whole domains, sometimes fractionally.

The functional significance of supported variants would require testing in a mouse model of USH2A disease (which exist for both USH2A and USH2C -- gene GPR98) but is difficult for any long gene. Thus alternative splicing is not a favorable object for study. Nonetheless, the 5 reported splice variants in human USH2A are worth further consideration, in particular an alternate splice with donor preceding exon 59 and acceptor within exon 64 would delete six Fn3 repeats (residues 3580–4121) in mouse numbering; a second variation involves expression of exon 71 in inner ear but not retina.

The current status of variant transcripts about S3743 in exon 56 can be studied by Blat in human and mouse with expression tracks open. No variant splices affecting this region have ever been reported to GenBank in either mouse or human as of July 2009.

>USH2A_hs_55-57 GLQPYTNYSFTLTACTSAGCTSSEPFLGQTLQAAPE GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR YTYKLEVKTGGGSSASDDYIVQTPMSTPEEIYPPYNITVIGPYSIFVAWIPP >USH2A_mm9_55-57 GLQPYTNYSFTLAVCTSVGCTSSEPCVGQTLQAAPQ GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWNPPERPNGLISQYQLRRNGSLLLVGGRDNQSFTDSNLEPGSR YIYKLEARTGGGSSWSEDYLVQMPLWTPEDIHPPCNVTVLGSDSIFVAWPTP

Structural significance

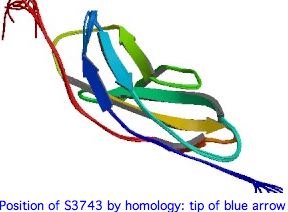

The 3D structure of the 22nd FN3 domain of USH2A could be evaluated using best-blastp to a structurally determined FN3 domain in PDB, then modelling the FN3 domain in question by submitting it to SwissModel with both S3743 and T3743. Here the percent identity to an already-determined structure is mediocre but perhaps still sufficient.

If the serine at 3743 is on the surface and involved in a binding interaction with a second (unknown) protein, then the effect of the 3743N substitution would be very difficult to evaluate because asparagine and serine are of similar bulk and polarity and the binding structures would be unlikely to have a PDB representative.

While S <--> N is a benign substitution at many positions in many proteins, at residue 3743 it appears that the hydroxyl lacking in asparagine is critical because, to the extent that any subsition at all is tolerated, here it is threonine. Bulk too may play a role because tyrosine is never seen.

The two best blastp hits at PDB of the S3743 region of USH2A are shown below -- quite weak but to FN3 domains of other proteins. The first match has threonine at position homologous to 3743, the second serine, so both models may have utility. In both cases the critical residue is in the final beta strand of an anti-parallel sandwich of sheets. Tandem FN3 pairs have been structurally determined for more dimly related proteins.

Note how the alignments below strengthens the case for the significance of the residue at 3743. It follows a conserved proline motif, part of a turn and not in a beta strand. The serine (resp threonine) then begins the last beta strand of the top anti-parallel sheet. The sidechain itself is not directly involved in the beta sheet hydrogen bonding scheme which uses the carbonyl and amide hydrogens. This turn and strand start are immensely conserved in FN3 domains -- many hundreds of billions of years -- even as many other regions have diverged beyond recognizability.

pdb|1X5L|A second Fn3 domain of ephrin receptor s EPHA8 Identities 29% Positives 47% USH2A GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNF----------TDKNLEPNSRYTYKLEVKTGGG V V R T+V L W PE+PNG++ +Y++ + E Q++ T L+P +RY +++ +T G 1X5L QV-VVIRQERAGQTSVSLLWQEPEQPNGIILEYEIK-----YYEKDKEMQSYSTLKAVTTRATVSGLKPGTRYVFQVRARTSAG beta strand 6 pdb|1WFO|A The Eighth Fn3 Domain Of Human Sidekick-2 SDK2 Identities 27% Positives 47% ...L.Pft.Y...v.act..G consensus of 35 USH2A FN3 repeats USH2A INSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRN--------GNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSRYTYKLEVKTGGG-SSASDDYIVQT + +T+V L W P PNG++ YQ++ + L S Q +T L+P S Y +++ +T G A++ +V T 1WFO VRTTSVRLIWQPPAAPNGIILAYQITHRLNTTTANTATVEVLAPSARQ-YTATGLKPESVYLFRITAQTRKGWGEAAEALVVTT beta strand 8

Normal function of usherin

A dozen recent papers on hearing and vision have illuminated the normal function USH2A gene product via its binding with other domains and proteins and related diseases, important progress but still not sufficient to explain how and whether specific fibronectin variants lead to disease phenotypes.

Protein binding partners of USH2A are important to identify because surface contacts in hetero-oligomers co-evolve and so have explanatory potential for point mutation and variation in USH2A. Prime suspects include gene products themselves causing vision and hearing disorders. The gene LCA5, responsible for Leber congenital amaurosis V, encodes lebercilin, a 697 residue protein involved in centrosomal and cilia. Lebercilin and usherin do not interact directly but rather via NLP encoded ninein-like protein at the basal bodies of the photoreceptor connecting cilia.

Both lebercilin and ninein-like have extended coiled-coil domains in addition to SMC (an ancient centrosomal chromosome segregation domain) and EF-hands (in NLP). NLP has not surfaced to date in vision disorders, perhaps because of an essential role in mitosis, a notation somewhat at variance with its moderate rate of divergence. Alternative alleles of NLP -- and indeed LCA5 through chain transitivity of binding effects -- could compensate or exacerbate pathogenic alleles of USH2A.

Coiled-coil helices could plausibly bind to an established groove on USH2A fibronectin domains though this has not been established as the NLP interaction mode. USH2A also has laminin, EGF and PDZ1 domains which commonly interact with other proteins.

Laminin domains of usherin, residues 518-1052 in short form numbering, bind the 7S domain of type IV collagen, with USH2B mutations in loop b but not loop d abolishing this binding. These experiments need to be revisited using full length usherin.

The PDZ1-binding domain at the usherin C-terminus (cytoplasmic side) bind both whirlin (DFNB31) and the scaffold protein harmonin (causative for USH1C) at synaptic terminals of both retinal photoreceptors and inner ear hair cells (and within stereocilia). Cell adhesion molecules in pre- and post-synaptic membranes keep the synaptic cleft in proper register. Harmonin plays an integrative role across numerous proteins involved in type 1 Usher diseases, so this linkage to USH2A (and VLGR1 of USH2C) begins to explain how mutations in so many genes can give rise to such similar disorders.

Functional significance

Here human individuals homozygous for N3743N could be examined for early loss of hearing accompanied by loss as teenager of mid-periferal and night vision. Heterozygous S3743N compounded by a different USH2A mutation (known autosomal recessive causative) on the other chromosome 1 allele would also imply pathogenicity of N3743N.

Alternatively, since mouse has an moderately conserved orthologous 22nd FN3 domain at 77.5% identity including the serine, the effect of S3743N could be considered as a knockin. Even if the mouse gene did serve as a valid disease model for other alleles, symptoms for S3743N might or might not develop within the 2-3 year lifespan of laboratory mouse.

For the immediate term, comparative genomics is best available guide. Here it is clear that S3743 is immensely conserved over several billion years of evolutionary time in those clades observable via genome projects (transcripts are too rare in this long gene to sample species diversity further). This establishes that N3743 is not part of the acceptable reduced alphabet at this residue, though T3743 at one time appears to have been acceptable in the teleost ancestor (and indeed is retained to the present day in early diverging deuterostomes).

The difference alignment below of the exon containing S3743 shows overall conservation well above human proteome average but not extraordinary inflexibility at most positions. The fibronectin portion is evolving as well, no doubt through both drift, internal adaptive change, and co-evolutionary response to binding partner change.

Consequently S3743N -- despite its innocuous appearing nature (ie high Dayhoff matrix score) is likely to have significant non-adaptive impacts on either standalone structure of USH2A protein or its interaction with other proteins in the basement membrane. If selective pressure did not exist to maintain S3743, then what would account for its constancy despite copious observed variation in nearby residues over the same time span?

The large number of known loci throughout this protein that give rise to Usher Syndrome 2A suggest that not only does this protein play an exceedingly important structural role highly sensitive to seemingly minor mutation perturbations but also that no other gene product is able to compensate for its absence.

Of the 22 known disease-causing point mutations that within a FN3 domain, none is situated at a position homologous to S3743; the closest are P1212L at -3 of the 2nd FN3 domain, T3571M at +10 of the 20th FN3 domain, and T4425M at +10 of the 29nd FN3 domain.

In a sense, the real mystery with USH2A is how nearly all of its 33 FN3 domains could be so mission-critical that a slight perturbation in one cannot be compensated for by the strength of interaction in the remaining 32. Here the overall 3D structure is not known, yet surely it is very extended like all other studied fibronectin proteins, for example titin which extends for 20,000 angstroms, longer than a entire bacterial cell. Titin has 33,000 residues made up of 195 immunoglobulin Ig and 132 fibronectin FN3 domains. By proportionality then (as the domains types are of similar size), USH2A would extend outside the cell for nearly 3,000 angstroms.

The answer may be in the observation that Usher 2A is not noticed at birth unless hearing is tested and vision problems arise only in the second decade. With sensory systems we are perhaps more sensitive to functional loss than at other basement membrane sites of USH2A expression.

Speculatively, USH2A protein may not be replenished over the lifespan in the basement membranes of these terminally differentiated cell types and slight dysfunctionalities might lead to slight enhancements in turnover rate, over decades leading to excessive loss of cell matrix structure and perhaps death or inability of the hosting cell to carry out its other functions.

Comparative genomics

The alignments below show the orthologous exon from 46 species. While no variation at S3743 occurs at any mammal or bird USH2A, lizard is possibly anomalous with asparagine in its best matching FN3 domain as are some fish with arginine and early-diverging deuterostomes and cnidaria with threonine.

However the lizard situation is bioinformatically uncertain because the the 3 exons centering on 3743 are missing from the UCSC genome assembly upon whole USH2A blat, whereas the best matching domain is present in AAWZ01000661 upon tblastn at wgs, with the asparagine supported by 4 raw trace reads. The putative relevent exon itself is unexpectedly diverged, causing it to fall to the bottom of the alignment tree in conflict with phylogenetic position. It further has an unusual one residue deletion 6 amino acids prior to 3743.

Consequently the Anolis feature may not represent the orthologous exon of a functioning gene copy. However it provides support for the idea that some fibronectin domains in some species can tolerate asparagine at paralogous position. Thus while N3743, if valid, detracts only mildly from story of invariant S3743 (with T3743 tolerated), the divergence time with mammals is some 310 myr ago.

The arginine anomaly in four telost fish but not zebrafish cannot be read or assembly error. S3743R is not at all a conservative substitution. Parsimoniously, it represents a single event in a late diverging clupeomorph fish, Since it has persisted in descendent lineages, it may represent adaptive change. Note shark has S3743, as do amphioxus and sea urchin. Lamprey genome is incomplete here.

In summary, S3743 has been fixed for billions of years of branch length within mammals and beyond. The reduced alphabet here is very restricted (outside of rapidly evolving teleost fish) with T3743 probably ancestral and nearly the full extent of admitted variation. Note asparagine codons, like threonine, lie a single base transition away and so experience no need for two mutational steps and the consequent intermediate barrier. This implies a small amino acid with hydroxyl at this position is critical to proper functionality of USH2A. Hydrogen-bonding capability (eg asparagine) is likely not sufficient in a substituent for serine.

Thus S3743N, though it could be an adaptive functional innovation, is most likely a maladaptive mutation. The symptoms of Usher Syndrome 2A are the likeliest outcome in the homozygote given the situation at the many known other disease alleles, though the penetrance and age of onset remains unpredictable.

As a cautionary note, a distinction must be observed between significant impact to normal function and significant impact to fitness. For example, sickle-cell hemoglobin evidently disrupts normal protein function, yet it adds to fitness (malarial resistance) in the heterozygote. Here allele population statistics are illuminating. Prion disease complicates that: amyloid and dementia surely does not add to either normal function nor fitness yet age of onset of familial CJD is so late that harmful alleles rarely came into play during lifespans typical of almost all of human evolution. This has allowed certain lethal alleles to attain substantial frequencies through founder effect and drift.

............................................................^. hatch marks S3743 site

USH2A_homSap GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_panTro GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_gorGor GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_ponAbe GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEKQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_nomLeu GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQKFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_macMul GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_calJac GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLQPNSR

USH2A_tarSyr GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSPPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGTLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPHSR

USH2A_micMur GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSPPEKPNGLISQYQLRRNGTLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_tupBel GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPKKPNGLISQYQLSRNGTLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPDSR

USH2A_musMus GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWNPPERPNGLISQYQLRRNGSLLLVGGRDNQSFTDSNLEPGSR

USH2A_ratNor GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWNPPERPNGVISQYRLRRNGSLLLVGGRDDQSFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_dipOrd GVWVTPRHIIINSTAVELYWSPPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGSVLFLGGREEQMFTDTNLEPNSR

USH2A_cavPor GVWVTPRHTVINSTSVELYWSPPEKPNGLISQYRLSRNGTLLFVGGGEEQNFTDKHLEPNSR

USH2A_speTri GVWVTPRHMIINSTTVELYWSPPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGTLLLLGGSEERNFTDKHLEPNSR

USH2A_oryCun GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWTPPEKPNGLISQYQLNRNGIVVFLGGSKEQNFTDRNLKPNSR

USH2A_ochPri GVWVSPRHIVINCTAVILYWSPPEKPNGIISQYQLIRNETVLYLGSGKEQNFTDGNLEPNSR

USH2A_vicPac GVWVTPRHIIINPTTVELYWSPPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGTLVFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_susScr GVWVTPRHIIVNSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGTVVFLGGSEERNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_turTru GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGSLVFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_bosTau GVWVTPRHIVVNSTTVELFWSPPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGSLIFLGGSEEHNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_equCab GVWMTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSPPENPNGLISQYQLSRNGTLVFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_felCat GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSPPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGTLVFLGGNEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_canFam GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWNPPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGTLVFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_myoLuc GVWATPRHIIINATAVELYWRPPERPNGLISRYQLIRNGTSVFLGGSEDQHFTDHNLAPNSR

USH2A_pteVam GVWVTPQHIIINSTAVELCWSPPEEPNGLISQYRLSRDGNLVFLAGAEEHCFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_loxAfr GVWLTPRHIIINPTTVELYWSQPEKPNGLISRYHLRRNGTLVLLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_proCap GVWMTPRHIVINSTTVELHWSLPEKPNGHISQYRLRRNGTLVFQGGGEEQNFTDTNLEPNSR

USH2A_dasNov GVWVTPGHIIINSTTVELYWSQPEKPNGLISHYQLSRNGTLIFLAGREEQSFTDKNLEPNSR

USH2A_choHof GVWVTPQHIIINSTTVELYWSQPEKPNGLISQYQLSRNGTSVFQGGREEQHFTDKNLEPSSR

USH2A_monDom GVWSIPRHIIINSTTVELYWNEPEKPNGLISKYQLHRNGTVIFLGGREDQNFTDDSLEPKSS

USH2A_ornAna GVWSKPQHITVSSTTVELYWSQPEKPNGVISQYRLIRNGTEIFAGTRDSLNFTDDSLESNSR

USH2A_galGal GVWPKPHHIIVSSTEVEIYWSEPEIPNGLITQYRLFRDEEQIFLGGSRDLNFTDVNLQPNSR

USH2A_taeGut GVWPKPHHIIVSSTEVEMYWSEPEEPNGLITHYRLFRDGEQIFLGGSTARNFTDVNLQPNSR

USH2A_anoCar GVWSQPRHVIVSSKIVELYWDEPEEPNGIISLYRLFRNGEEIFMGGELNLNFTD-TVQPNNR 4 traces, not in assembly

USH2A_xenTro GVWSNPYHVTINESVLELYWSEPETPNGIVSQYRLILNGEVISLRSGECLNFTDVGLQPNSR

USH2A_tetNig GVWSKPRHLTVNASAVELHWDPPQQPQGLVSQYRLKRDGRAVFTGDHLQRNYTDAGLQPQRR

USH2A_takRub GVWSKPRHLIVTTAVVELYWDPPQQPHGHISQYKLKRDGQTVFTGDHDDQNYTDTGLRPHRR

USH2A_gasAcu GVWSSPRHVVINTSAVELYWDQPLQPNGHISQYRLNRDGDTIFTGDHREQNYTDTGLLPNRR

USH2A_oryLat GVWSKPRHLIINTSAVELYWDQPSQPNGLISQYRLIRDGLTVFTGARRDQNYTDTGLEPKRR

USH2A_danRer GVWSMPRHIQLNSSAVELHWSDPLKLNGLLSGYRLLRDGELVFTADGGKMSYTDAGLQPNTR

USH2A_calMil GIWPKPCHVIVNSSTVELYWTEPEKPNGIITQFRLLRDNAVIYTGTRRNRNYTDAGLQPDTR

USH2A_braFlo QEVSRPRFVVVSSTEIEVYWSEPGRPNGIITQYQLVRDGSVIYSGG--DMNFTDSGLTPSTT XM_002214612 aligns over 2807 aa

USH2A_strPur EGLMQPTHVVVSSTILELYWFEPSQPNGVITSYILYRDDELVYSGNNSVLTYVDTGLTPNTR XM_788345 aligns over 5030 aa

USH2A_nemVec SQQPAPVITVSSSRRLDLAWSPPDNPNGIILRYELYRNGTEVYRG--VIRGYNDTNLQPDTL XM_001638773 aligns over 3005 aa

USH2A_hydMag SQQGAPFVLFQTSRLINIGWFPPDNLNGILIKYELYRDRTKIFVG--LDNNYTDNNLKPYTY XM_002165140

............................................................^.

USH_homSap GVWVTPRHIIINSTTVELYWSLPEKPNGLVSQYQLSRNGNLLFLGGSEEQNFTDKNLEPNSR

USH_panTro ..............................................................

USH_gorGor .............................I................................

USH_macMul .............................I................................

USH_calJac .............................I...........................Q....

USH_ponAbe .............................I..................K.............

USH_nomLeu .............................I....................K...........

USH_turTru .............................I.........S.V....................

USH_tupBel .......................K.....I.........T...................D..

USH_susScr ..........V..................I.........TVV.......R............

USH_tarSyr .....................P.......I.........T...................H..

USH_micMur .....................P.......I.....R...T......................

USH_vicPac ............P........P.......I.........T.V....................

USH_felCat .....................P.......I.........T.V....N...............

USH_canFam ....................NP.......I.........T.V....................

USH_equCab ...M.................P..N....I.........T.V....................

USH_bosTau .........VV.......F..P.................S.I.......H............

USH_cavPor ........TV....S......P.......I...R.....T...V..G........H......

USH_speTri ........M............P.......I.........T..L......R.....H......

USH_oryCun ....................TP.......I.....N...IVV.....K......R..K....

USH_dipOrd ..............A......P.......I.........SV.....R...M...T.......

USH_loxAfr ...L........P........Q.......I.R.H.R...T.VL...................

USH_dasNov ......G..............Q.......I.H.......T.I..A.R...S...........

USH_choHof ......Q..............Q.......I.........TSV.Q..R...H........S..

USH_proCap ...M.....V........H.........HI...R.R...T.V.Q..G.......T.......

USH_musMus ....................NP..R....I.....R...S..LV..RDN.S...S....G..

USH_ratNor ....................NP..R...VI...R.R...S..LV..RDD.S...........

USH_myoLuc ...A........A.A.....RP..R....I.R...I...TSV......D.H...H..A....

USH_pteVam ......Q.......A...C..P..E....I...R...D...V..A.A..HC...........

USH_monDom ...SI...............NE.......I.K...H...TVI....R.D.....DS...K.S

USH_ochPri ....S....V..C.A.I....P......II.....I..ETV.Y..SGK......G.......

USH_ornAna ...SK.Q..TVS.........Q......VI...R.I...TEI.A.TRDSL....DS..S...

USH_galGal ...PK.H...VS..E..I...E..I....IT..R.F.DEEQI.....RDL....V..Q....

USH_taeGut ...PK.H...VS..E..M...E..E....ITH.R.F.D.EQI.....TAR....V..Q....

USH_xenTro ...SN.Y.VT..ESVL.....E..T...I....R.IL..EVIS.RSG.CL....VG.Q....

USH_anoCar ...SQ...V.VS.KI.....DE..E...II.L.R.F...EEI.M..ELNL....-TVQ..N.

............................................................^.

USH2A allele assessment by PolyPhen is not optimal

Despite 60 years of work that began in 1949 with E6V in sickle cell hemoglobin), it remains very difficult to accurately interpret observed coding variation in human genes in terms of disease. This is illustrated in the modern era in the Watson human genome, which is homozygous for known disease alleles in genes for Usher 1A and Cockayne syndromes, yet the individual remains asymptomatic at age 80. Consequently, the goal S3743N must be lowered from a definitive diagnosis to merely making the best interpretation that consideration of all current data allows.

The much-cited SNP evaluation tool, PolyPhen, works at a great disadvantage here because its algorithm uses only comparative genomics derived from blastp matches at SwissProt rather than from NCBI wgs and nr, here locating a meagre 6 homologs for USH2A vs 46 species here, resulting in a severely limited estimation of the reduced alphabet at 3743. Orthology is assumed, not established -- a highly problematic procedure since this could mix in lineage-specific FN3 domain gains and losses that later re-functionalized perhaps with divergence of constraints on the critical residue.

Sequences are also not considered in their phylogenetic tree context so cumulative supporting branch length time is an unavailable metric (eg PolyPhen treats sea urchin as equally informative as mouse). The fibronectin domain and its type (III) are not explicitly recognized by the algorithm and experimental domain literature -- and that of USH2A -- are ignored. Paralogous residues to S3743 in internal and external FN3 domains are thus not in the mix. Because of a 50% identity cutof, PolyPhen misses here diverged but still highly informative PDB structures.

Scoring the list of known Usher 2A Syndrome causative alleles that lie in USH2A fibronectin domains with PolyPhen gauge its accuracy, typically 70% correctly identified but here only 12 of 22 are scored correctly (55%), treating 'possibly damaging' as a miscall for reasons given elsewhere.

None of the clinically assessed FN3 mutations lie in the 22nd FN3 domain and none lie in internal paralog position to S3743. However 3 do lie in the conserved patch about 3743 in paralogous domains. The tendency for residues important to normal function to occur in patches has not yet been systematically evaluated here or in PolyPhen but may be useful in weighting allele interpretation.

S 3743 T 0.364 benign naturally occuring Q 4592 H 1.308 benign A 2795 S 1.317 benign S 3743 N 1.348 benign uncertain pathogenicity T 3976 M 1.644 possibly damaging S 3743 R 1.729 possibly damaging naturally occuring P 3504 T 1.757 possibly damaging A 2249 D 1.828 possibly damaging T 4337 M 1.835 possibly damaging R 2354 H 1.909 possibly damaging T 4439 I 1.933 possibly damaging L 4795 R 2.018 probably damaging T 4425 M 2.050 probably damaging T 3571 M 2.050 probably damaging S 4054 I 2.064 probably damaging G 3895 E 2.274 probably damaging R 3124 G 2.429 probably damaging uncertain pathogenicity P 4232 R 2.621 probably damaging R 4115 C 2.654 probably damaging uncertain pathogenicity P 4818 L 2.724 probably damaging Y 4487 C 2.758 probably damaging P 1059 L 2.846 probably damaging uncertain pathogenicity P 1212 L 2.846 probably damaging W 3521 R 3.902 probably damaging

PolyPhen thus treats S3743N as borderline benign based primarily on S->N innocuousness; its algorithm proceeds without a valid description of the reduced alphabet at this position (S,T: hydroxyl) nor knowledge of the subsequent fixation of S in amniote. It is far from ideal to use BloSum transition matrices which are broad averages over unrelated proteins and so greatly enriched for bland transitions such as S-->N which indeed are generally neutral (indeed by design of the genetic code).

In summary, algorithmic approaches to coding SNP classification inevitably fall short (see 1,2) of using all available information, leading to suboptimal annotation. Such tools have value in quick screening of millions of alleles for flaming anomalies but are not particularly useful for specific genes because curational judgement on more extensive information can always outperform them.

This is illustrated above in comparative genomics products not available to these tools but very useful in making the best possible annotation call. While this can never attain perfect reliability, it is still exceedingly important to make all-out use of bioinformatics in view of the high costs and time needed for experimental validation, in view of disease burden in an era of imminent genomic medicine.