Opsin evolution: ancestral introns

See also: Curated Sequences | Alignment | Informative Indels | Ancestral Sequences | Cytoplasmic face | Update Blog

Introduction to intron analysis

Introns within coding regions of opsin genes can potentially provide an independent (or supplemental) means of organizing known opsins into orthologous families and and classifying new ones with ambigous alignment clustering. This becomes especially important as the universe of opsins expands to include rhabdomeric opsins within deuterostomes, ciliary opsins within protostomes, and novel opsins from cnidarians which are otherwise difficult to place (or even distinguish from rhodopsin superfamily non-opsins and other GPCR).

In most lineages, intron pattern is extremely conserved over great evolutionary distances (eg human to anemone), even when amino acid sequence is not. Changes are classified as rare genetic events (RGEs) and can supplement sequence change in determining gene and species tree topology. Other RGEs relevent to opsins include coding indels (insertion or deletion of amino acids) and gene order rearrangements along a chromosome (synteny).

RGEs are characters that can be used in gene tree analyses and reconstruction of ancestral states. Each type of RGE has its own intrinsic time scale that makes it useful on particular aspects of opsin evolution over commensurate time frames. Intron patterns are extremely conserved, making them useless over mammalian, even vertebrate, time scales (stay the same) but are appropriate over Eumetazoa. Indels too are quite conserved (being constrained by membrane width in transmembrane proteins) so are informative within opsins over shorter intervals (eg Pancrustacea). Gene order is only moderately conserved within Bilatera, more commonly it is completely washed out.

All RGEs are potentially subject to homoplasy -- two or more separate events with the same outcome. However, rare events are seldom fixed. Homoplasy amounts to a low probability squared. With an event rate, say for intron gain in a coding gene from last common ancestor with cnidarian to human, not approaching one per billion years per gene, with the average protein having 450 residues and with introns having 3 possible insertion phases at each residue, homoplasy is a total non-issue for the entire proteome (provided intron gain is random).

Intron loss is more frequent but still rare in most lineages. Here there is greater opportunity for homoplasy (notably in Insecta) because the 3' end of the gene is more susceptible to repeats of the mechanism (apparently recombination with retroprocessed mRNA). More intensive taxon sampling can often distinguish timing of separate events. This requires genome sequencing because mature transcripts have lost all information about introns. Uncommonly transcripts retain introns and pseudogenes contain information about ancestral introns. (However opsins, not being transcribed in the germ line to any extent, rarely give rise to retro pseudogenes.)

The vast majority of introns were created in single-celled eukaryotes in the pre-Cambrian. Modulo intron gain and loss, these have descended unchanged in position and phase to the present day. Intron drift (movement by a few residues) does occur but is greatly over-stated when annotation of homologs is sloppy. Intron positions are randomly sited with respect to protein domains. Falsely stated to occur at domain boundaries, some authors are confused by domain iteration (internal tandem duplication of exons by improper recombination) and by domain shuffling.

The first task in utilizing introns as evolutionary characters is to resolve intron gain from loss. This can only be done up to parsimony because the proposition of modelling mechanistically uncertain processes a billion years back in highly diverged lineages (for maximal parsimony) is preposterous. However, provided evenhanded taxonomic sampling is available, the event history is seldom in doubt (rare events squared).

Consequently, the ancestral intronation can be reliably worked out for almost any protein at each species divergence node. While of some intrinsic interest, the main application is evolution of large gene families. Here paralogous branches can have quite different histories. This allows differentiation of these branches from each other at a time when linear sequence homology might become an uncertain guide.

For example melanopsins and encephalopsins are intronated quite differently, even though ultimately both are descended from a single gene. At the time of Ur-bilateran divergence, the intronation of melanopsins has completely coalesced within protostomes but not quite with deuterostomes and not at all with ancestral intronation of ciliary opsins. Consequently the Ur-bilateran had at least two opsins (ie the opsins of fruitfly and human are only homologous, not orthologous). To date, all cnidarian and ctenophore opsins have been single exons genomically or processed transcripts.

Consequently no informative outgroup exists for bilaterans and ancestral opsin intronation cannot be worked out further. (Nematostella normally retains ancestral exons but apparently not here; intron gain is otherwise too rare past this divergence node to account for bilateran opsin intronation.)

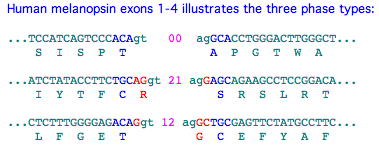

Intron location and phase for dummies

The intron pattern consists of two parameters, location and phase (fractional codon distributed across two exons):

Location is easy to specify homologically in opsins because they contain numerous invariant or near-invariant residues sprinkled along their length that provide multiple internal anchors to alignments. The main potential difficulty occurs near an indel (insertion or deletion). However indels are rarely fixed in the core region of opsins because the transmembrane helices (3.4 residues per turn) do not tolerate disruption of their bundle association geometry or membrane spanning lengths.

Similarly the cytoplasmic face and extracellular loop regions, with the exception of CL3, are too short or too engaged in the conserved interactions of signaling and its regulation. Indels in the amino and carboxy termini, which in many opsin classes are extended and poorly conserved, are a different matter; however exons in these regions tend to be extensions of core exons or narrowly lineage-specific.

It's quite possible for more or less the same intron location to arise repeatedly (convergent evolution), especially when 'same' is slightly muddled by indel ambiguity. However phase determination can often disambiguate the near-proximity issue. Here we must pause to review MolBio 101 because many opsin papers exhibit total unawareness of the phase concept:

Three possibilities exist for intron phase: In phase 00, the splice donor (GT in all known opsins) follows immediately after last triplet codon of an exon and the splice acceptor (AG in all known opsins) immediately precedes the first codon of the next exon. In phase 12, an extra basepair follows the last completed triplet codon and precedes the GT start of the splice donor; two extra base pairs (which fill out the split codon and preserve reading frame) precede the acceptor codon. In phase 21 introns, the overhang is 2 bp at the donor end, balanced by 1 bp overhang at the acceptor, together forming a new 3 bp triplet codon.

>MEL1_homSap Homo sapiens (human) Gq 483 NM_033282 melanopsin OPN4 0 MNPPSGPRVPPSPTQEPSCMATPAPPSWWDSSQSSISSLGRLPSISPT 0 0 APGTWAAAWVPLPTVDVPDHAHYTLGTVILLVGLTGMLGNLTVIYTFCR 2 1 SRSLRTPANMFIINLAVSDFLMSFTQAPVFFTSSLYKQWLFGET 1 ...

It's useful to indicate phase information within the fasta representation of a sequence. That's done here by line breaks between exons with associated phase overhangs shown by numbers. These numbers are ignored by the vast majority of web software tools so the extra characters do not to be purged before blast queries etc. This format is well-suited to incomplete genome projects because the unit of recovery is typically a whole exon. By convention, the initial methionine is preceded by a 0 even though it is generally part of a larger 5' UTR. Similarily the stop codon asterisk is followed by a 0 even though it is almost always part of a longer 3' UTR. One last convention: the 'extra' amino acid formed by 12 or 21 introns is assigned to the 2 side of the exon break. It's often given incorrectly in Blast output because that tool is not aware of exon breaks and often extends alignments past them into a translated intron.

Normally, phase is determined by aligning by blastn of a transcript (processed already by the cell to remove introns) against genomic sequence. If genomic is not available, the transcript can be reliably intronated in most instances by comparison to a phylogenetically close orthologous gene from a genomic species.

For example, full length transcripts are available for various opsins from the amphioxus Branchiostoma belcheri. However the genome project is not there but over in Branchiostoma floridae. So the B. belcheri proteins need to be placed within the B. floridae assembly, which is conveniently done using Blat on the UCSC genome browser. Exon boundaries are then read off from the alignment details page using 3-frame translation in a second web browser tab at Expasy to ensure smooth reading frame joins and uBlastx against the opsin collection in a third tab to monitor alignment. This process provides a predictive intronation of the presumptive ortholog.

This won't be accurate if B. belcheri has gained or lost introns since the two species diverged. However, outside of certain rogue species, introns typically have a "half-life" of perhaps 5 billion years of branch length, many multiples of the divergence time here. (They're much more conserved than amino acid sequence.) Consequently the inferred gene model will be correct 99% of the time. However every sequence in the Opsin Classifier that originated in a genome project was independently intronated within that project, never by homology. And some species without genome projects (like Platynereis) have the occasional large genomic contig with an opsin.

In practise, it is easy to make small mistakes in assigning phases to genes, especially when percent identity is remote from the alignment query. That's because GT and AG are common dinucleotides and sometimes multiple options seem viable (preserve reading frame). Of course, there's much more to splice sites than just two dinucleotides so sometimes those additional properties must be used to sort out the possibilities (gene prediction software tools carry sophisticated versions of these rules). Usually only one possibility works consistently across the comparative genomics spectrum within a given class of opsins.

It turns out that in post-lamprey deuterostomes not a single case of intron gain or loss can be documented in any of the 14 opsin gene trees (recall each sequence set is maximally phylogenetically dispersed). Since each tree contains several billions of years of branch length, the overall event rate for opsins in this clade is lower than 1 per 50 billion years of evolutionary clock time. Intron conservation of opsins is not atypical -- intron gain and loss is know to be very infrequent (but not zero) across the entire vertebrate proteome.

However other issues must be considered such as alternative splicing, intron sliding, NAGNAG ambiguity, asymmetric frequenciy ratios of phase types (00 is most abundant), mechanisms and relative frequency of gains and loses, hotspots of predisposition, likelihood of convergent evolution, migration out of GT-AG to minor splice forms and so forth. Alternative splicing is irrelevent to opsins because their membrane transiting properties are intolerant -- alternative transcripts are presumably just transcriptome noise. Intron sliding does occurs rarely but most literature claims for it have been debunked. Acceptor ambiguity is real but not seen yet in opsins where indels are disfavored.

There is a general predisposition to enhanced intron loss distally (3') due to recombination with processed mRNA; mechanisms of intron gain are a bit cryptic and -- like everything else -- cannot be assumed the same across all of Metazoa. General trends need not be applicable to the opsing gene family,. Homoplasy hotspots may have some relevance to insect opsins; these apply to inaccessible ancestral sequence so their basis cannot be inferred than contemporary forms.

Using the full inventory of metazoan genome projects, over 350 phylogenetically dispersed opsins in all opsin families have been intronated using direct genomic comparison when possible and homological annotation transfer when not. The error rate is not zero; anomalies needing revisiting are concentrated in 12 and 21 introns and in opsins without close homologs. When a gene model is fragmentary, only half the splice site may be available so that validation of the other half is lacking. In some assemblies, there seem to be sequencing errors that don't allow introns where they are required to avoid premature stop codons.

The scientific literature on intron antiquity is hopelessly muddled due to wild speculation in the pre-informatics era. Today we know that the vast majority of human introns are very old and stable, dating back to early unicellular eukaryotes (eg introns in human SUMF1 are shared with diatom). Consequently most exons were already well entrenched at the time of Eumetazoan emergence and experienced little gain or loss outside of rogue lineages (notably sea urchins, tunicates, nematodes, fruitflies). We expect most deuterostome introns to be present in at least some species of ecdysozoa, lophotrochozoa, and cnidaria; this has been validated recently in the case of Nematostella.

The practical consequence for opsins is that most-- but not all intronation -- occured prior to the major gene duplications and subsequent divergence. To the extent this is valid, a core set of intron location and phases will be common to all opsins. After these are removed, the remaining later-created introns can sometimes guide the reconstruction of the gene tree (independently of sequence alignment). That is, if a series of gene duplications takes place over time, a series of one-off intron creations during the same timeframe will affect only the descendent sub-clade.

Here we expect melanopsins and cilopsins to be distinuished by shared introns from peropsins, neuropsin and RGRopsins. The latter group of opsins, due to their highly diverged nature, have never been persuasively assigned a position in the overall opsin gene tree. However this endeavor requires an extensive collection of cnidarian and earlier branching genomes. To date, opsin candidates in these species have either been intronless (presumably retroprocessed genes like olfactory GPCR) or have not had determinable introns (arose as transcripts).

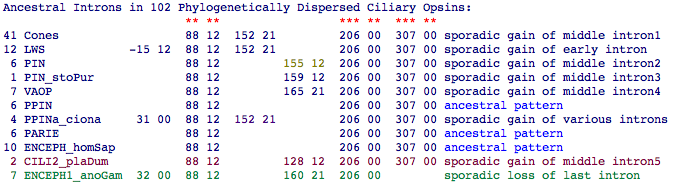

Ancestral ciliary intronation

Let's consider first the intron situation in ciliary opsins and whether we can unambiguously determine the ancestral intron pattern at the time of Urbilatera or even Urmetazoa. We'll use common sense parsimony rather than maximal likelihood methods because these simply bury their subjectivity within rarely discussed model assumptions that aren't likely to consistently hold across this vast time and clade scale -- higher taxa sampling density on long branches is the best way to test and improve ancestral intron prediction.

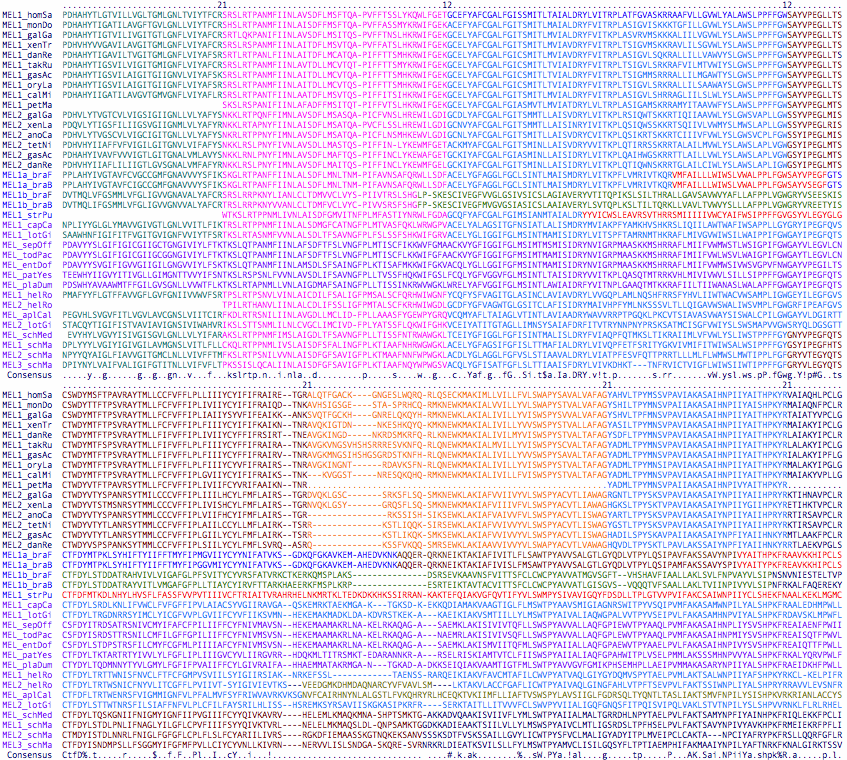

Two detailed examples in Annotation Tricks section explain how the Opsin Classifier sequence collection can be used in conjunction with uBlast to determine whether exon breaks of a given opsin agree with another. Let's look now at the full set of all known ciliary opsins, knowing in advance that those in protostomes will ultimately arbitrate the deuterome situation as outgroup until such time as definitive relevently intronated cnidarian opsins are located.

It's apparent that all 109 deuterostome ciliary opsins in our current 11 orthology class collection (namely RHO1 RHO2 SWS2 SWS LWS PIN VAOP PPIN PARIE ENCEPH TMT (with 4 classes RGR PER NEUR and MEL held out as intron pattern specificity controls) exhibit a single conserved intronation pattern across the human to echinoderm time scale. There are some significant events, all of which predate lamprey divergence, such as the extra intron in LWS opsins. Here the gene tree structure can provide outgroups capable of distinguishing intron gain from intron loss (LWS experienced a gain). This gene tree is reliably enough known from many publications or can be quickly generated with common software such as ClustalW from the vastly expanded collection in the Opsin Classifier.

In Lophotrochozoa, the situation is much more limited with just two Platynereis opsins, of which one is well-characterized by experiment and the other is directly intronatable. Perhaps with targeted sequencing effort, new cdna, additional bioinformatics, or more complete genomes, homologs will emerge in Capitella, Helobdella, Aplysia, Lottia, Schmidtea, or Schistosoma but it appears that ciliary opsins are severely depleted in this large clade. These species do provide intronated opsins of melanopsin amd peropsin class.

In Ecdysozoa, 3 ciliary opsins have been established in Anopheles and Apis whereas they are completely ruled out in the (truly finished) Drosophila genome. The list of genomic species with a ciliary opsin (presumably a single orthologous locus) can be readily extended to Culex, Aedes, Tribolium, Bombyx, Rhodnius, Acyrthosiphon, Heliothis and Daphnia (the only non-insect to date with ciliary opsins). However gene loss seems to have happened repeatedly (or current coverage is insufficient); the gene cannot be found in Nasonia, Ixodes, and other species with completed genome projects. Nematodes have no opsins of any kind.

To procede with the actual work of ancestral intron determination, it's helpful to first reduce the number of sequences to a smaller set of proxy sequences that retain all the information but less of the clutter. Once it has been determined that introns in RHO1 are exactly conserved in location and phase in the phylogenetically diverse set of 14 sequences representing human to lamprey nodes, the task shifts to comparing RHO1 introns with other opsins so a single representative RHO1 sequence suffices. (The set of 14 RHO1 in the reference collecion is already an immense reduction of many hundreds available in over-sampled fish and placental mammals.) Proxy sequences can also carry coding indel and synteny information.

These sequences can be optimized in various ways to allow more reliable homological comparisons of intron positions to other opsins, including remotely related proteins. Various options exist, such as ancestral reconstruction, consensus sequence, profile sequence, basal diverging species sequence (lamprey), or single-species-consistent set (frog would work). However almost all ciliary opsin homology classes evolved after tunicate but prior to lamprey divergences, meaning earlier ancestral sequence cannot be reconstructed. The accuracy of ancestral sequences is not experimentally validatable; errors arise especially in co-evolving but non-adjacent amino acids.

Determination of ancestral ciliary opsin introns is feasible in vertebrates because gain and loss of introns is exceedingly rare proteomewide per billion years of branch length. This greatly minimizes homoplasy concerns. It soon emerges unambiguously that the ancestral ciliary opsin had 3 introns separating its 4 exons. These are denoted in the summary table as 88 12 FATLG, 206 00 FTVKE, and 307 00 MMNKQ where the notation provides homologous position relative to bovine rhodopsin numbering in a gapped alignment, intron phase, and five residues for text-search localization within alignments.)

Note the ciliary opsin from lophotrochozoan Platynereis plays a key role in establishing the third intron which at this point appears lost in the stem of ecdysozoa (insects plus crustacean). However, the story is not so simple because many opsin classes also contain one or two 'sporadic' introns of limited gene tree distribution and so specific only to later developments in that orthology class). The only exception here is 152 21 which cuts across all rod and cone opsin classes. There is some positional uncertainty in regions of heavy loop gapping (eg 155 12 and 159 12 difference could be a gapping effect) and coincidental convergences are not impossible (the 152 21 intron in the heavily altered PPINa_ciona may be one).

In this view, it takes 10 intron gains and 1 loss to account for the data, rather at odds with received wisdom about those relative rates. That number could be reduced by admitting a degree of positional or phase drift in the interior region that would lump events; however that mechanism lacks support outside this gene family despite claims to the contrary. Hypothetically, an insertional hotspot existed here along an ancestral stem during the condensed era of gene duplication. A stem species may have had a higher rate of intron gain and loss than we see in most species today (rogue species such as Drosophila and Ciona are hyperactive examples). The exact sequence of events may never be resolved because of an insufficient number of extant species from the amphioxus-lamprey stem.

The intron data in ciliary opsins, as in so many genes, conflicts with 1R and 2R whole genome duplication scenarios in early deuterostomes. That cannot have played any role in any post-encephalopsin, post-amphioxus ciliary opsins which instead are simply sequentially nested intron-preserving segmental duplications. The data also conflict with sweeping theories of ectopic propagation of established visual systems via blocks of gene duplication and neofunctionalization.

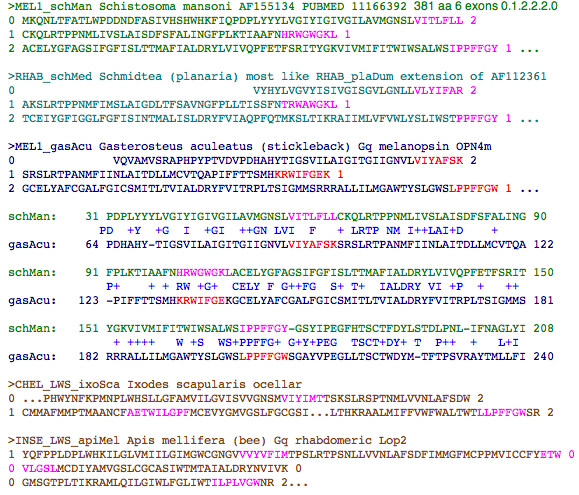

Ancestral melanopsin intronation

Arthropod rhabdomeric opsins are another arena where 'too many' sequences have been determined in insects without genomes. Here too the gene tree is well established and a reliable enough ancestral proxy sequence feasible. That's not the case for ciliary opsins in lophtrochozoa, cnidaria, and early diverging deuterostomes; here the full sparse set of individual sequences must be retained. This mixes noisy contemporary opsin sequences with filtered ancestral sequences -- not necessarily a problem but something to keep in view at the interpretative stage.

However it turns out that ciliary, rhabdomeric, and 'retinal isomerase' opsins introns in Bilatera may have completely disjoint sets of introns -- any common ground is far more deeply ancestral. Hence they can be considered separately. Further, no significant variation whatsoever occurs in intron pattern within any orthology class (these were established independently), though intron pattern alone is not sufficient to distinguish all orthology classes.

Melanopsins are better represented in all three major branches of Bilatera. The overall intronation history is complicated but not excessively so given the tens of billions of years elapsed. Common ground can readily be recognized between ecdysozoa and vertebrate and, as illustrated below, between lophotrochozoa and vertebrate melanopsins.

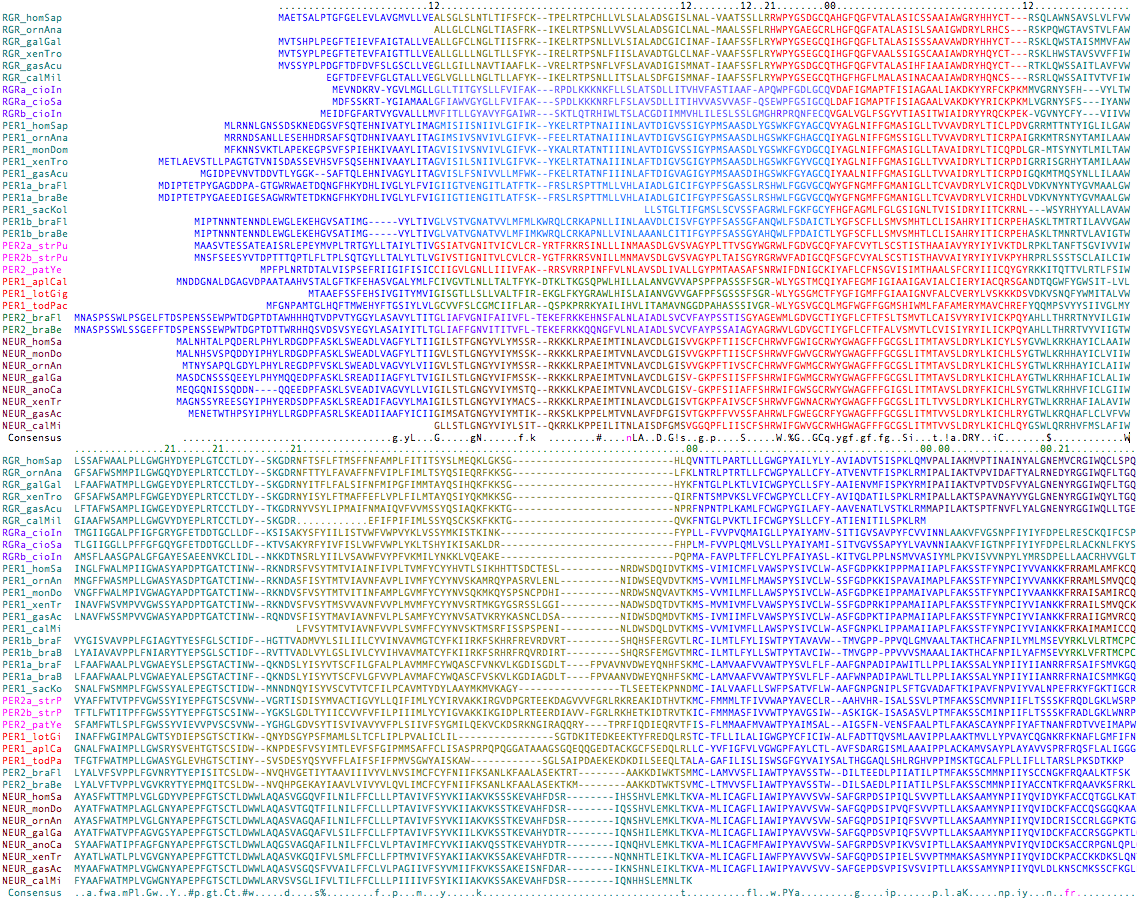

Ancestral peropsin, neuropsin and RGRopsin intronation

Peropsins, RGRopsins, and neuropsins are commonly taken as a self-contained subfamily in terms of both sequence clustering and their set of unique introns, though exactly how they are nested with respect to other opsin classes is not completely clear. Exon breaks are colored in the accompaning image with phases shown in the top line. Four molluscan peropsins to serve as outgroup to the otherwise entirely deuterostomic collection, proving their presence in Urbilatera (which was already apparent from their deep rooting). Gapping ambiguity can be a serious issue when introns happen to fall in non-transmembrane loops where length is not necessarily well constrained; some regions lack satisfactorily conserved biflanking anchoring residues.

The first exon break of phase 12 is shared by all 35 members and hence is ancestral. A long second exon, shown in red and also ending in phase 12, is also universally shared distally (though in vertebrates shortened by 3 residues). In all but 3 deeply diverging peropsins, it is broken into two exons in 6 different ways utilizing the 3 different phases. A third universal exon break occurs near the end of the protein. It too can have various internal introns.

These sporadic introns follow within-class blastp cluster associations, though some shared endpoints suggest alternative scenarios. It's important to realize most parsimonius scenario is not necessarily the actual history -- which is a one-off sequence of events for any given gene family, not a statistical ensemble. It would be especially helpful to locate intronated cnidarian opsins in this group.

Neuropsins have a two residule indel in the EXC2 loop region with reliable conserved flanking CTLDWWLAQASVGGQVF; that length is seen again in cone and rod opsins. Therefore the indel is an insertion event and does not serve to unite peropsins and rgropsins. Neuropsins are expressed in eye, brain, testes and spinal cord to accomplish unknown functions.

Interestingly, two sea urchin peropsins share identical introns with a scallop peropsin studied in biochemical detail and so by implication also bind 11-cis-retinal and are Go-hyperpolarizing in their signaling. That can be predicted as well for PER2_braFlo (Amphiop3) of Branchiostoma. Beyond the cognate signaling partner, if any, is unclear.

Refinement of ancestral intronation

Melanopsin introns are quite well-behaved. The set of 36 includes 15 from lophotrochozoa (of which 8 are directly intronatable) but none from ecdysozoa (which have opsins likely specialized derived from melanopsin). Only the introns within the core melanopsin can be compared because confidence in homologous alignment breaks down elsewhere. Deuterostome melanopsin cores all have 7 exons (with the exception of oddities in amphioxus and sea urchin). The first 4 have strong support in both position and phase in the protostomal outgroup, making them ancestral for Urbilatera. The fifth is somewhat ambiguous because it begins within a loop of highly variable length and ends in a conserved site but without outgroup support. The sixth and seventh introns are either ancestral or lost to fusion in the outgroup stem. In summary, ancestral melanopsin was present in Urbilatera and its intron signature could be used to decisively validate cnidarian homologs.

We're now in a far better position to analyze putative ciliary opsins in cnidaria and sponges (which might be seriously diverged in primary sequence). Nematostella in particular is quite conservative overall in terms of ancestral intron retention (minimal gain and loss relative to human). Opsins could be an exceptional gene family in that regard, but that primarily makes sense for gene copies derived initially by retropositioning (as in olfactory rhodopsins), with all old introns lost and perhaps 1-2 new ones subsequently gained.

A weak blast match to authentic opsins and proven expression in a photoreception cell is insufficient to establish a given candidate gene as an opsin: a slow-evolving generic GPCR might also give similar alignment quality and other signaling processes take place even within a specialized cell type. Without diagnostic residues, appropriate introns, and informative indels, the evidence could be very circumstantial. In fact, there may be ciliary pre-opsins within the rhodopsin GPCR superfamily which are not engaged in photoreception themselves but survive as members of the immediate sister gene family. That could account for the excessive numbers being reported in cnidaria vis-a-vis their visual requirements and also their independent intronation. This scenario seems to orphans them in terms of agonist however.

Reference data

Ancestral Introns in Ciliary Opsins: all data

* ** ** * *** ** * *** * * *** *

RHO1_homSa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_monDo . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_bosTa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_ornAn . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_galGa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_xenTr . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_neoFo . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_latCh . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_anoCa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_petMa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_letJa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_geoAu . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_leuEr . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_calMi . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO1_takRu . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO2_galGa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO2_anoCa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO2_neoFo . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO2_latCh . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO2_gekGe . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

RHO2_geoAu . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_ornAn . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_utaSt . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_taeGu . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_neoFo . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_galGa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_xenTr . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_geoAu . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_takRu . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS2_gasAc . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_homSa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_monDo . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_anoCa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_utaSt . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_taeGu . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_galGa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_neoFo . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_xenLa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_geoAu . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_danRe . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

SWS1_oryLa . . . 1 88 12 2 152 21 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

LWS_homSap 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_monDom 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_ornAna 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_galGal 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_anoCar 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_xenTro 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_takRub 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_gasAcu 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_petMar 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_letJap 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_geoAus 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

LWS_neoFor 1 -15 12 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 4 206 0 5 307 0

PIN_galGal . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 155 12 3 206 0 4 307 0

PIN_utaSta . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 155 12 3 206 0 4 307 0

PIN_podSic . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 155 12 3 206 0 4 307 0

PIN_pheMad . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 155 12 3 206 0 4 307 0

PIN_xenTro . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 155 12 3 206 0 4 307 0

PIN_bufJap . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 155 12 3 206 0 4 307 0

VAOP_galGa . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 165 21 3 206 0 4 307 0

VAOP_anoCa . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 165 21 3 206 0 4 307 0

VAOP_xenTr . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 165 21 3 206 0 4 307 0

VAOP_danRe . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 165 21 3 206 0 4 307 0

VAOP_rutRu . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 165 21 3 206 0 4 307 0

VAOP_takRu . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 165 21 3 206 0 4 307 0

VAOP_petMa . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 165 21 3 206 0 4 307 0

PPIN_anoCa . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PPIN_xenTr . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PPIN_petMa . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PPIN_letJa . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PPIN_ictPu . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PPIN_oncMy . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PPIN_danRe . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PPINa_cioI 1 31 0 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 5 206 0 7 307 0

PPINa_cioS 1 31 0 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 5 206 0 7 307 0

PPINb_cioI 1 31 0 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 5 206 0 7 307 0

PPINb_cioS 1 31 0 2 88 12 3 152 21 . . . 5 206 0 7 307 0

PARIE_utaS . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PARIE_anoC . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PARIE_xenT . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PARIE_takR . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PARIE_gasA . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

PARIE_danR . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

CILI2_plaD . . . 1 88 12 2 128 12 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

CILI1_plaD . . . 1 88 12 2 128 12 . . . 3 206 0 4 307 0

PIN_stoPur . . . 1 88 12 . . . 2 159 12 3 206 0 4 307 0

ENCEPH_hom . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH_mon . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH_gal . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH_ano . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH_gas . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH_xen . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH4a_t . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH4b_t . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH4_br . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH5_br . . . 1 88 12 . . . . . . 2 206 0 3 307 0

ENCEPH1_an 1 32 0 2 88 12 . . . 3 160 21 4 206 0 . . .

ENCEPH2_an 1 32 0 2 88 12 . . . 3 160 21 4 206 0 . . .

ENCEPH_aed 1 32 0 2 88 12 . . . 3 160 21 4 206 0 . . .

ENCEPH_cul 1 32 0 2 88 12 . . . 3 160 21 4 206 0 . . .

ENCEPH_tri 1 32 0 2 88 12 . . . 3 160 21 4 206 0 . . .

ENCEPH_bom 1 32 0 2 88 12 . . . 3 160 21 4 206 0 . . .

ENCEPH_dap 1 32 0 2 88 12 . . . 3 160 21 4 206 0 . . .

ENCEPH_api 1 47 0 2 80 21 3 122 21 4 233 12 5 272 0

See also: Curated Sequences | Alignment | Informative Indels | Ancestral Sequences | Cytoplasmic face | Update Blog